October 07, Colombo (LNW): In its latest assessment of Sri Lanka’s economic prospects, the World Bank has called for far-reaching structural reforms to secure long-term growth and help lift millions out of poverty.

The institution’s recommendations come as the island nation emerges from a devastating financial collapse that saw it default on its external debt and experience soaring inflation and widespread hardship.

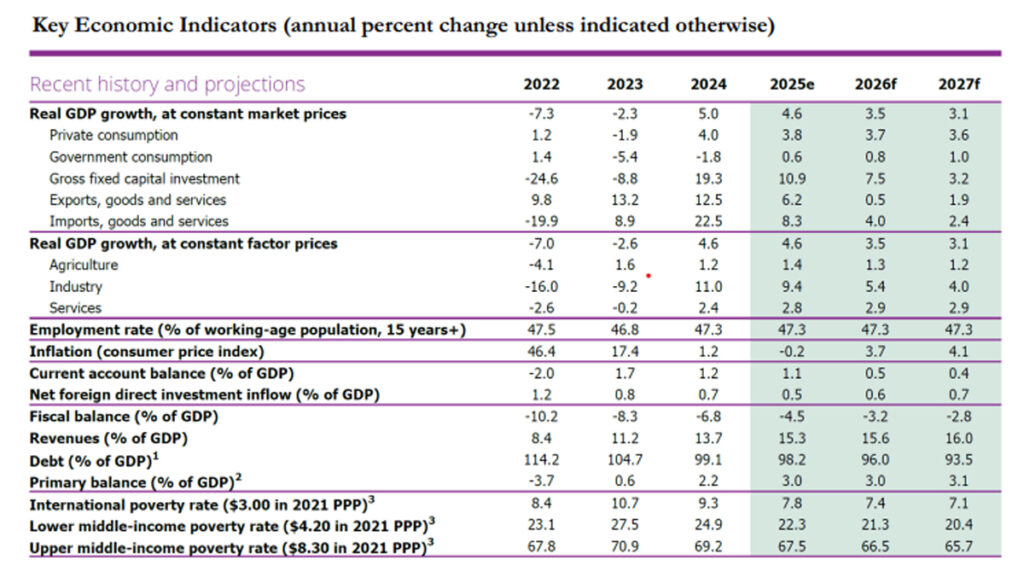

According to the World Bank’s newly released Development Update, Sri Lanka’s economy is on a fragile recovery path, with projected growth of 4.6 per cent in 2025, potentially slowing to 3.5 per cent the following year.

However, sustained progress will depend on how effectively the country implements key reforms in trade, labour, land ownership, and public finance.

One of the central messages of the report is the need for Sri Lanka to liberalise its “factors of production”—namely labour and land—both of which are currently bound by outdated legal frameworks and state control.

Richard Walker, the World Bank’s Senior Country Economist for Sri Lanka, noted that the labour market is governed by legislation dating back several decades, creating layers of bureaucracy and uncertainty for investors. “Employers are often deterred by the complexity of the labour regulations, which in turn hampers job creation. This rigidity also disproportionately affects women’s participation in the workforce,” he said, describing female employment as an underutilised area of potential.

On the issue of land, the World Bank highlighted that approximately 80 per cent of land remains under state control, managed by a maze of overlapping authorities with unclear mandates. This situation stifles agricultural productivity and makes private investment in land development difficult. “Clarifying land ownership and improving access is critical not only for farmers but for long-term sustainable land management and urban development,” Walker added.

Public investment is another area the Bank scrutinised, urging the government to be more selective and strategic. Rather than launching new projects indiscriminately, authorities are advised to complete existing infrastructure works, shift focus to essential maintenance, and employ a more data-driven approach to planning. Shruti Lakhtakia, Country Economist for Sri Lanka, emphasised the need for a more integrated public investment management system that streamlines project selection, appraisal, and execution.

Fiscal discipline remains a major concern. While recent tax increases have led to higher revenues, Sri Lanka’s massive debt burden leaves little room for wasteful spending. The report underlined the importance of redirecting expenditure towards projects with demonstrable value and long-term benefits.

Reforming the public sector was also identified as crucial. Over time, Sri Lanka has built a bloated public service, with frequent hiring sprees—often politically motivated—adding thousands to the payroll without corresponding increases in productivity.

Though average public wages are not exceptionally high, the sheer number of government employees is unsustainable for a country of Sri Lanka’s size. The Bank also criticised the current wage structure, which consists of a confusing mix of allowances and basic pay, calling for simplification and rationalisation.

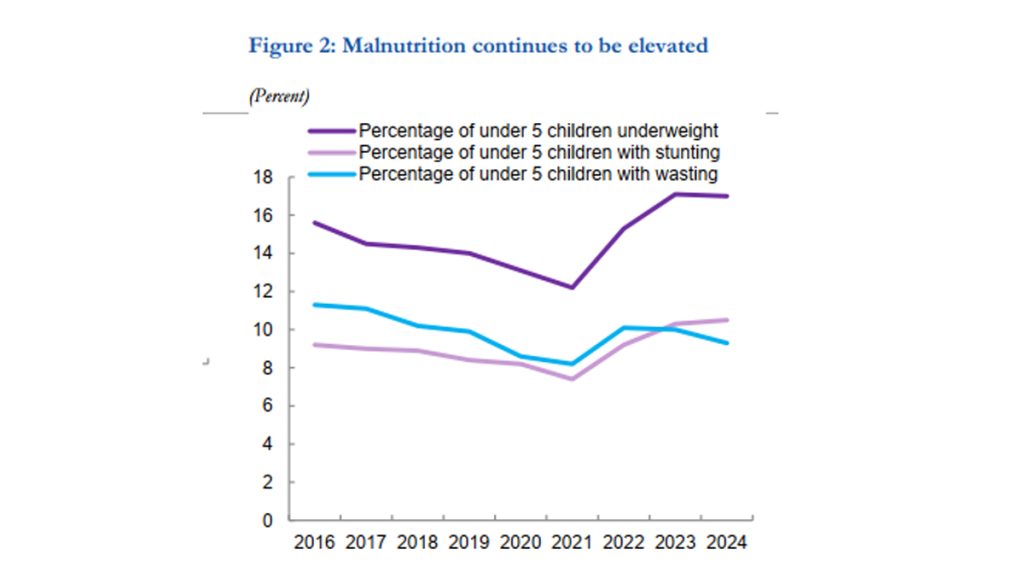

A key backdrop to these recommendations is Sri Lanka’s recent economic collapse. Years of mismanagement, combined with excessive money printing and ill-timed interest rate cuts, triggered a severe currency devaluation and eventually a sovereign default. The consequences were dramatic: inflation soared, food prices surged, and poverty rates ballooned.

Though the central bank has since introduced stabilisation measures, concerns remain. Analysts warn that inflation could continue to rise at an annual rate of 5–7 per cent if fiscal and monetary discipline wavers again, particularly if currency depreciation is used to meet inflation targets.

Despite these risks, there are signs of gradual recovery. The World Bank projects that poverty levels, which spiked dramatically during the crisis, could fall from 24.9 per cent in 2024 to 22.3 per cent in 2025. Still, a significant portion of the population—estimated at around 10 per cent—remains vulnerable and at risk of slipping back into poverty if economic conditions deteriorate.

The report concludes with a cautious note of optimism. While Sri Lanka has begun laying the groundwork for economic recovery, the real test lies in whether it can push forward with difficult but necessary reforms. By creating a more open, transparent, and investor-friendly environment, the country may yet find a sustainable path to prosperity.