ScienceAlert : After a decade of work, researchers are closer than ever to a key breakthrough in kidney organ transplants: being able to transfer kidneys from donors with different blood types than the recipients, which could significantly speed up waiting times and save lives.

A team from institutions across Canada and China has managed to create a ‘universal’ kidney, which can, in theory, be accepted by any patient.

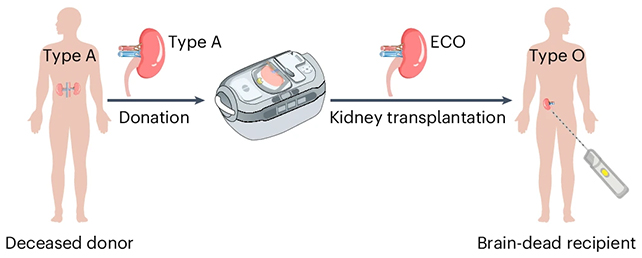

Their test organ survived and functioned for several days in the body of a brain-dead recipient, whose family consented to the research.

“This is the first time we’ve seen this play out in a human model,” says biochemist Stephen Withers, from the University of British Columbia in Canada. “It gives us invaluable insight into how to improve long-term outcomes.”

Related: Surgeons Resuscitate ‘Dead’ Heart in Life-Saving Organ Transplant to Baby

As it stands today, people with type O blood who need a kidney usually have to wait for a type O kidney to become available from a donor. That accounts for more than half the people on waitlists, but because type O kidneys can function in people with other blood types, they’re in short supply.

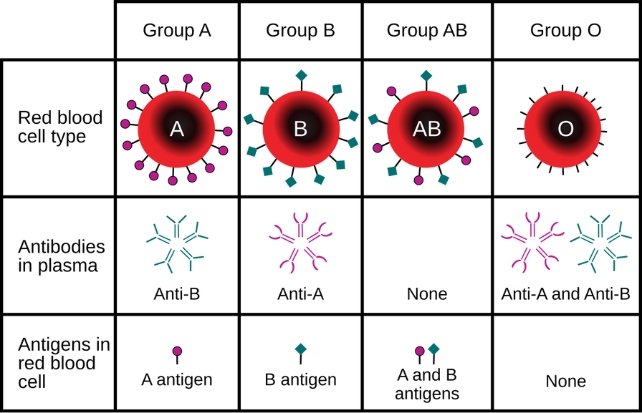

Blood type (or blood group) is determined, in part, by the ABO blood group antigens present on red blood cells. Antibodies in our blood plasma detect when a foreign antigen marker is present (InvictaHOG/Public Domain/Wikimedia Commons)

While it is currently possible to transplant kidneys of different blood types, by training the recipient’s body not to reject the organ, the existing process is far from perfect and not particularly practical.

It’s time-consuming, expensive, and risky, and it also requires living donors to work, as the recipient needs time to be prepped.

Here, the researchers effectively converted a type A kidney into a type O kidney, using special, previously identified enzymes that strip away the sugar molecules (antigens) acting as markers of type A blood.

The researchers compare the enzymes to scissors working on the molecular scale: by snipping off part of the type A antigen chains, they can be turned into the ABO antigen-free status that characterizes type O blood.

“It’s like removing the red paint from a car and uncovering the neutral primer,” says Withers. “Once that’s done, the immune system no longer sees the organ as foreign.”

Related: Your Blood Type Affects Your Risk of an Early Stroke, Study Reveals

There remain plenty of challenges ahead before trials in living humans can be considered.

The transplanted kidney did start to show signs of type A blood again by the third day, which led to an immune response – but the response was less severe than would usually be expected, and there were signs that the body was trying to tolerate the kidney.

The statistics surrounding this issue are pretty stark: at the moment, 11 people die waiting for a kidney transplant each day, in the US alone, and the majority of those are waiting for type O kidneys.

It’s a problem that scientists are tackling from multiple angles, including making use of pig kidneys and developing new antibodies. Broadening the number of compatible kidneys these people can have promises to make a significant difference.

“This is what it looks like when years of basic science finally connect to patient care,” says Withers. “Seeing our discoveries edge closer to real-world impact is what keeps us pushing forward.”

The research has been published in Nature Biomedical Engineering.