In Sri Lanka right now, before you’ve woken up, you’re losing.

Power cuts that run late into the sweltering nights steal hours of sleep as the fans cease; whole families waking up sapped from the months-long trial of shuffling their lives around daily blackouts after the country went bankrupt and essentially ran out of fuel.

There are long days to be lived; work days, errands to be run, daily essentials to be bought at twice the price they had been last month.

All this, you’re starting a little more broken than you were last week.

Once you’ve had breakfast – eating less than you used to, or perhaps nothing at all – the battle to find transport beckons.

In the cities, fuel queues curl around entire suburbs like gargantuan metal pythons, growing longer and fatter by the day, choking roads and crushing livelihoods.

Tuk-tuk drivers with their eight-litre tanks are forced to spend days lining up before they can run hires again, for 48 hours perhaps, before they are forced to rejoin the queue, bringing pillows, changes of clothes and water to see them through the ordeal.

For a while, middle- and upper-class folk had brought meal packets and soft drinks for those queuing in their neighbourhoods.

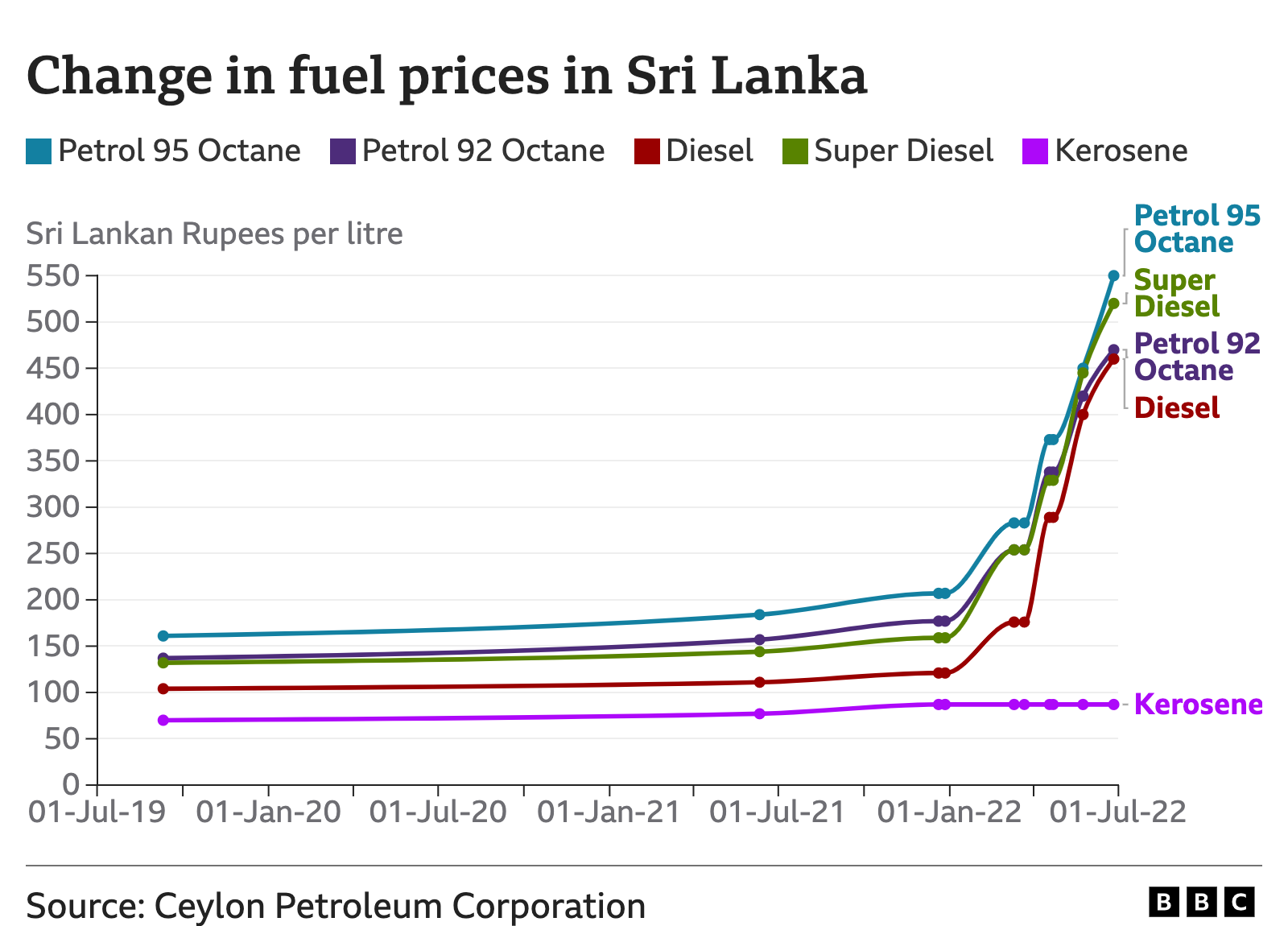

Lately, the cost of food, of cooking gas, of clothes, transport, and even what electricity the state will allow you to have, has sky-rocketed so egregiously as the rupee’s value plummeted, that even largesse from the moneyed has been in short supply.

In working-class neighbourhoods, families have begun to band together around wood fire stoves, to prepare the simplest of meals – rice, and coconut sambol.

Even dhal, a staple of the diet all over South Asia, has become a luxury. Meat? At three times the price it used to be? Forget it.

Fresh fish was once abundant and affordable. Now, boats can’t go out to sea, because there is no diesel. The fishermen that can go out sell their catch at vastly inflated rates to hotels and restaurants out of reach to most.

Sri Lanka: The basics

- Sri Lanka is an island nation off southern India: It won independence from British rule in 1948. Three ethnic groups – Sinhalese, Tamil and Muslim – make up 99% of the country’s 22 million population.

- One family of brothers has dominated for years: Mahindra Rajapaksa became a hero among the majority Sinhalese in 2009 when his government defeated Tamil separatist rebels after years of bitter and bloody civil war. His brother Gotabaya, who was defence secretary at the time, is now president.

- Now an economic crisis has led to fury on the streets: Soaring inflation has meant some foods, medication and fuel are in short supply, there are rolling blackouts and ordinary people have taken to the streets in anger with many blaming the Rajapaksa family and their government for the situation.

A majority of Sri Lankan children have now been forced to subsist on a diet with almost no protein. This is a crisis that has hit on every level from the macroeconomic to the molecular.

Are children’s brains, their organs, their muscles, their bones, getting what is required? Milk powder, most of which is imported, has barely been seen on market shelves for months.

The UN is now warning of malnutrition and a humanitarian crisis. For many here, the crisis has been roiling for months.

Those who can find rides generally commute on buses and train carriages bursting with evermore passengers.

Young men cling for their lives on the footboards, while the mashed throng inside gasps for air.

For decades Sri Lanka has failed to invest appropriately in its public transport, while the island’s wealthier residents continued to complain about the indiscipline of bus and trishaw drivers.

There is a growing view that it’s this perceived disdain for regular people from both the political and financial elites that has brought the nation to its knees. And yet it’s the lower-middle and working classes that must bear the worst of the economic collapse.

- ‘Living in my car for two days to buy fuel’

- Sri Lanka: ‘I can’t afford milk for my babies’

- What’s behind Sri Lanka’s petrol shortage?

- How war heroes became villains

Private hospitals continue to function, albeit less well than they used to. In North Central Anuradhapura, a 16-year old who had suffered a snakebite died as his father rushed desperately from pharmacy to pharmacy to look for the anti-venom the public hospital had run out of.

The healthcare sector can no longer afford many lifesaving medicines. In May, a jaundiced two-day-old died after her parents could not find a trishaw to take her to hospital.

As economists have pointed out, it is the sweeping tax cuts of 2019 – lobbied for and cheered on by many corporate and professional groups – that contributed to emptying Sri Lanka’s coffers, and helped bring the nation to this brink.

On the black market, fuel can still be bought at vastly inflated prices, some of it to run the larger private vehicles, and home electricity generators.

Lower down the economic ladder, people attempt to buy bicycles to make trips into work, and find the exchange rate has put even that form of transport out of reach.

It had been the worst of the power cuts that set off Colombo’s major protests, late in March. Back then, the 13-hour daily outages had left a nation exhausted in the hottest weeks of the year.

That fatigue had sparked widespread fury, and a crowd of thousands descended on the eastern Colombo suburb of Mirihana, where the president resides.

Of all the demonstrations in the country over the past year, this was perhaps the most visceral. A man in a motorcycle helmet made a speech railing at the political forces, clergy and media that had delivered the nation into the hands of what was now widely perceived as simultaneously the most self-serving and inept government here in generations.

Later, that man, Sudara Nadeesh, was beaten brutally by the police and arrested, along with several dozen others who suffered the same violent fate.

Sri Lanka had been strung up in a 26-year civil war, but even through that unspeakably violent stretch, the island has never had a president so close to the military’s top brass as former defence secretary Gotabaya Rajapaksa.

The south has found out in the past few months, what northerners have known for decades: dissent is routinely met with state violence.

In recent months largely peaceful protesters have had live rounds shot into their midst, tear gas has been indiscriminately fired at crowds in which small children were present. In queues for essentials, the mildest shows of displeasure have been met with brutal beatings.

Police say some officers suffered injuries when stones were thrown, but as protesters have lost lives, or ended up in hospital, the police response has been viewed as being wildly disproportionate.

On social media, politicians offer sympathy, posting photos of the public’s hardship while asking for change. This has mostly only inspired more outrage. Was it not the politicians who led us here?

And yet, while nationwide protests have called for the removal of the president and his cohort, they remain obstinately in place, their perceived disdain for the public’s will evident in the backroom deals that many feel continue to poison the island’s politics.

The same leaders accused of crashing Sri Lanka into this ravine insist that only they can lift the island out again, and the policies they devise are met with sharp criticism.

There is now a concerted push, for example, to send more Sri Lankans overseas to work as housemaids, drivers and mechanics in the Middle East, with those emigrants expected to send their earnings home.

This may only deepen the hardship of many of its most vulnerable citizens, as poor Sri Lankans with no hope of finding local employment are forced to leave their families for nations in which they have few protections and little agency. One anthropologist online described this vision for Sri Lanka in stark terms: “the vampire state”.

By evening in Sri Lanka’s crisis, you’re drained beyond imagination. Beyond the almost impossible commute because of the lack of petrol and diesel, the everyday functioning of a workplace has itself become a relentless onslaught of crises, with supply chains having broken down, most potential customers having long since refused to spend on anything but essentials, and staff failing to show up.

Then late-night power cuts come again, and you survive on lighter evening meals with each passing week, unable to buy enough food for your home, unable to cook what little you’ve bought, unable to give your parents their medication, or your children the education they deserve.

Schools are presently shut, as there is no fuel to take them. Classes are online for the third year running.

The government continually fails to deliver what little it’s promised, relatives and neighbours call to ask for money you don’t have to spare, the police and military bear down on what little hope remains, and through all this you’re still grateful, because many around you have it so much worse.

Last week, a mother threw herself and her two children into a river.

Every day, a fresh heartbreak.

Andrew Fidel Fernando is an award-winning author and journalist, based in Sri Lanka.