By Adolf

The recent US tariff announcement, according to IPS research, has reignited debate on the real burden of trade barriers. While headlines reference a “20% tariff” on key imports, the effective rate faced by Sri Lanka is significantly higher — closer to 28–30% when weighted across products, sectors, and tariff structures. Understanding this gap is critical for policymakers and exporters.

Why 20% Isn’t Really 20%

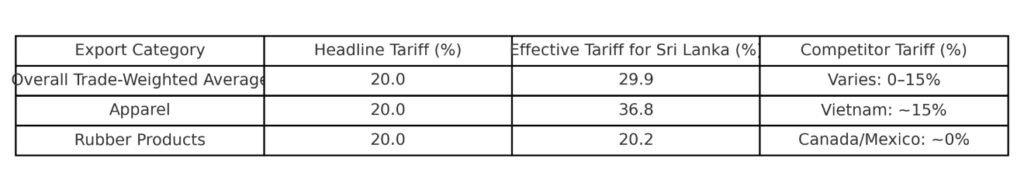

Tariffs are rarely applied as a single flat rate. The “headline” 20% applies to a narrow set of goods, but sector-specific surcharges, product classifications, and exemptions for certain trading partners push the trade-weighted effective rate much higher.

For Sri Lanka, the US effective tariff rate will rise to 29.9% from 7 August 2025, compared to just 10.2% in April 2025 under the MFN regime. Apparel exports — our largest category to the US — will face 36.8%, while rubber products will face 20.2%. Competitor countries such as Canada, Mexico, the EU, and Japan enjoy preferential access through trade deals, leaving Sri Lanka at a distinct disadvantage.

Impact on Sri Lanka’s Economy

Economic modelling shows that under a 30% tariff scenario, Sri Lanka’s real GDP could shrink by 0.082% (with full employment) or by 0.222% if unemployment rises. Apparel exports to the US could fall by over 44%, and rubber exports by 63%, as buyers shift to lower-cost suppliers.

Even under the so-called “20%” tariff, the impact remains severe: apparel exports could drop 12.1% (USD 220.8 million loss) and rubber exports by 42%. These shocks would ripple through the economy, hitting employment — especially unskilled women in apparel — and reducing household incomes.

The Reciprocity Risk

The danger is not only in the tariffs Washington imposes, but in the reciprocal tariffs Colombo may feel compelled to apply on US goods. Reciprocity is standard in trade, but it can backfire on smaller economies.

If Sri Lanka applies a 20% reciprocal tariff while retaining para-tariffs like CESS and PAL, US exporters will face barriers — but so will our own industries that rely on imported inputs. For example, removing para-tariffs on US soymeal as part of a concession could boost imports by 40%, lowering poultry feed costs but potentially flooding our market with cheap US meat and dairy, hurting local producers.

Modelling suggests a 15% reciprocal tariff — combined with selective para-tariff removal — could actually expand Sri Lanka’s GDP by 0.038%. But beyond that threshold, the risks outweigh the benefits.

Policy Takeaway

Headline tariffs understate the real burden. Sri Lanka’s effective tariff exposure is well above 20%, and reciprocity without careful targeting could damage key domestic sectors. Negotiating a lower reciprocal rate — ideally 10–15% — while safeguarding sensitive industries is essential.

India may have ended up with rates above 40%, but with President Trump, anything is possible. He is quick to forgive and forget — and we could even see India’s rate drop below the “20%” mark. In trade, as in politics, nothing is ever truly final.