August 17, Colombo (LNW): Interest rates in Sri Lanka have begun to rise again in June 2025, following a controversial rate reduction the previous month, as the country’s financial system shifts under the weight of conflicting pressures.

Official figures indicate a subtle yet significant upward movement in deposit rates, overnight borrowing costs, and interbank call money rates—signs of a tightening liquidity environment amid growing concerns about reserve depletion and monetary mismanagement.

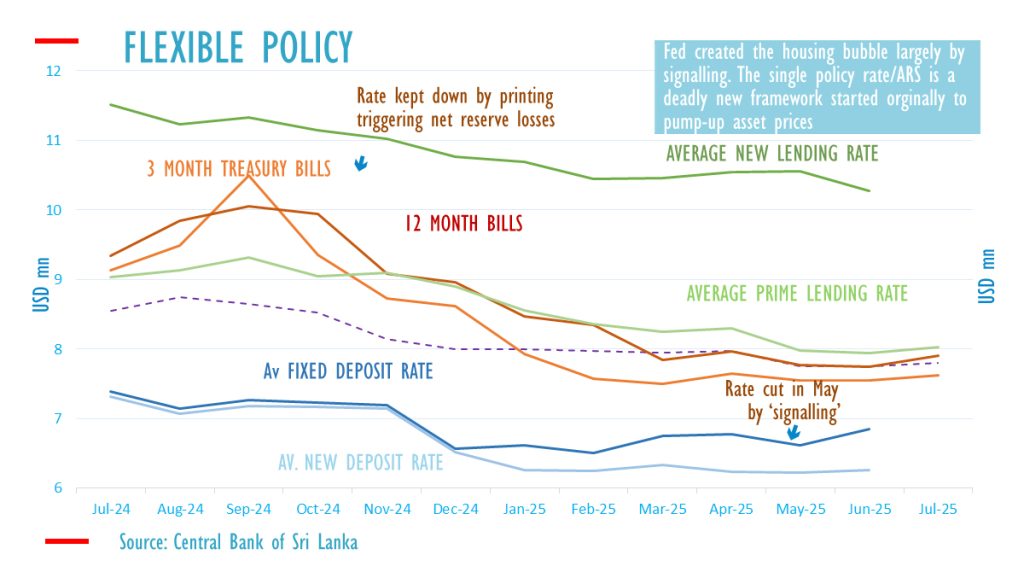

The uptick in deposit rates comes at a time when banks are under increasing pressure to attract fresh funds to support rising credit demand, a trend linked to the economy’s slow emergence from a prolonged period of instability. After a currency collapse and subsequent fiscal tightening, credit is beginning to expand again—but funding this expansion requires a stronger deposit base.

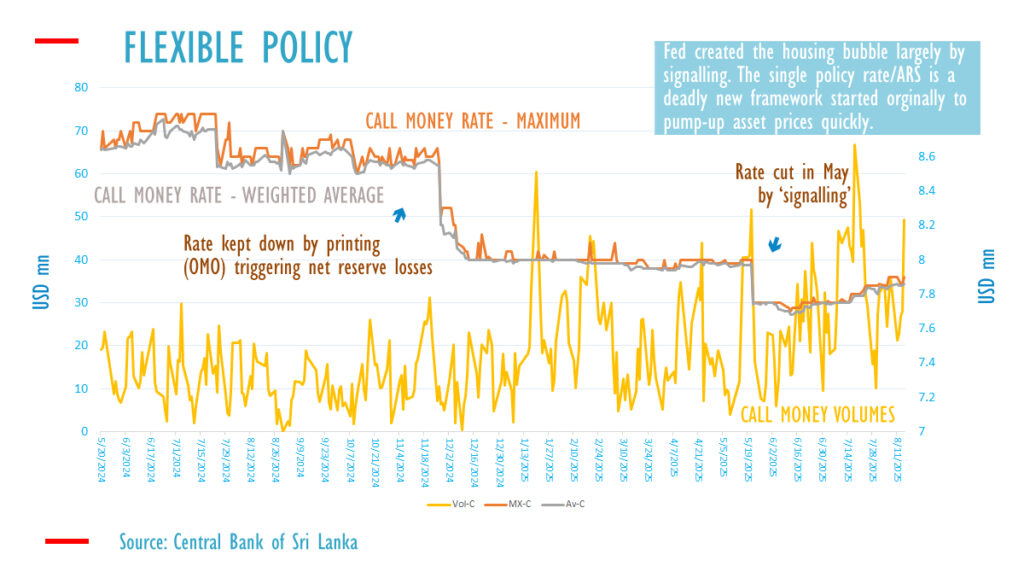

Interbank markets, particularly the call money segment where banks lend to each other without collateral, have seen both interest rates and volumes increase after an initial dip in the wake of May’s rate cut. This shift suggests a reawakening of interbank activity, albeit within a constrained liquidity environment now defined by what analysts call a “scarce reserve regime.”

Under such a regime, central bank liquidity is no longer freely available. Instead, banks must settle overnight imbalances through actual deposits or by curbing credit expansion. While this can encourage more disciplined financial behaviour, it also raises the cost of short-term borrowing and puts pressure on banks to compete more aggressively for depositors—hence the rising rates.

The Central Bank’s own data show that average new lending rates ticked upward through June, following an initial decline. This could reflect a short-lived response to the previous rate cut or be the result of increased competition, leading to narrower margins across the banking sector. While narrower margins are often seen as a sign of improved efficiency, they may also discourage investment in low-yield government securities.

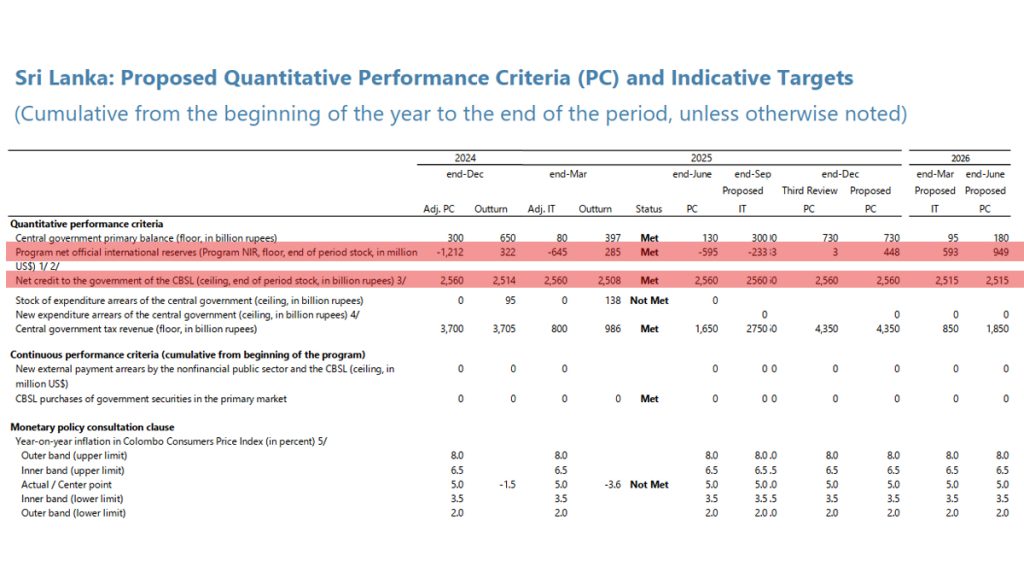

Economists caution that Sri Lanka’s monetary policy continues to be burdened by structural flaws. In the past, similar liquidity strategies—particularly efforts to maintain an artificially low policy rate—have led to rapid currency depreciation, foreign reserve losses, and eventual sovereign default. Despite having temporarily stabilised its foreign currency reserves through tight policy, the government is once again facing difficulty due to the central bank’s dominant role in managing foreign currency transactions.

In recent months, the Treasury has relied on the central bank to sell dollars to meet external debt obligations, a practice some critics argue exposes the country to renewed risk. Without a firm commitment to deflationary policy and current account discipline, such as under previous International Monetary Fund (IMF) agreements, fears are growing that the nation could slip into a second default.

The problem is compounded by the central bank’s continued reliance on a single policy rate—a method originally designed in the West to combat asset deflation in the aftermath of housing bubbles. While such an approach was meant to stimulate investment and protect markets, its long-term adoption in Sri Lanka has contributed to systemic imbalances, including inflationary pressures and a weakened interbank market.

Calls are mounting for a return to a more robust monetary framework—specifically a wide corridor scarce reserve regime—which allows short-term interest rates to rise and fall naturally in response to liquidity conditions. Under such a system, monetary authorities have greater flexibility to defend currency stability without distorting long-term rates or over-relying on external borrowing.

Historically, attempts to narrow the interest rate corridor—reducing it from 150 to 100 basis points, for instance—have been linked to several currency crises and, eventually, the country’s default on international debt. Experts now warn that without fundamental changes in liquidity management and reserve accumulation strategies, Sri Lanka’s economy remains vulnerable.

In the past, the government attempted to cover external financing needs by borrowing heavily through international bonds and syndicated loans rather than adjusting domestic policy. These approaches, viable only when credit ratings were higher, are no longer feasible.

As economic conditions remain delicate, Sri Lanka’s policymakers face a critical choice: pursue structural reform in monetary operations and restore market-based discipline, or continue on a path that risks repeating past mistakes with even less room to manoeuvre.