Demands are intensifying for the Sri Lankan government to reveal the burial site of Tamil political prisoners who were brutally tortured and murdered by Sinhalese inmates at Welikada Prison over two days, four decades ago. Campaigners are also urging that an international investigation, overseen by independent forensic experts, be initiated to uncover the truth and ensure justice.

Tamil political activists and the families of the murdered prisoners are calling for a comprehensive inquiry into the killing of 53 Tamil detainees, which occurred amid a wave of anti-Tamil violence during the infamous ‘Black July’ riots of 1983. These killings were allegedly carried out with the tacit approval—or at least the complicity—of prison authorities.

“Where Are Their Graves?” – The Call for International Accountability

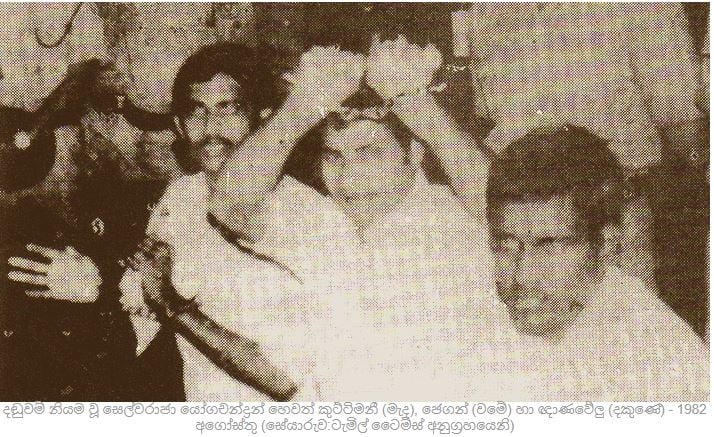

“Where did the government of the time bury my father and the others they killed? None of us know what became of their bodies. All we are asking is for an international investigation to be conducted into this massacre and for the perpetrators to be held accountable,” said Yogachandran Madiwannan, son of Selvarajah Yogachandran—better known as Kuttimani—who was among the victims of the Welikada Prison massacre.

Speaking in an exclusive interview, Madiwannan recalled how he learned of his father’s death through a radio broadcast while living in an orphanage in India, having fled Sri Lanka. The government, he said, never officially informed the family.

“After my father and the others were murdered by Sinhalese inmates, the government concealed the crime. How did they die? Was there even a proper funeral? Where are their graves? We were told nothing. Even today, we are left with unanswered questions,” he said in a trembling voice. He was just 12 years old at the time.

Burned at Borella Cemetery

According to independent investigations and eyewitness testimonies, the bodies of the slain prisoners were loaded onto a prison vehicle, transported to the public cemetery in Borella, dumped into a pit at a concealed location, piled with firewood, and burned.

Prominent civil rights advocate and former Member of Parliament M.K. Sivajilingam, who has persistently campaigned for Tamil rights, also insists that the current administration has both the authority and the obligation to launch an independent inquiry into the massacre—an atrocity that has been suppressed by successive governments for over 40 years.

“Every government since then has covered this up. The present government claims to be investigating concealed crimes—then let it investigate this mass killing as well. These prisoners were under judicial custody, which means they were under the protection of the state. It is irrelevant which government was in power then or now; the state must be held accountable,” Sivajilingam stated.

Both Madiwannan and Sivajilingam agree that a truly impartial investigation can only be ensured with the involvement of international experts, and that the Sri Lankan government alone cannot be trusted to carry it out transparently.

“The international community must intervene to investigate this crime thoroughly. Only then might we learn what truly happened to the bodies,” said Madiwannan.

Despite the unearthing of mass graves across the island, including in the North and East, investigations into such sites have remained informal or have been deliberately stifled. The Welikada massacre has now passed through 12 successive governments led by 9 different presidents. Recently, the seventh mass grave in Sampur was uncovered, underscoring the pervasiveness of such atrocities.

The First Wave of Killings

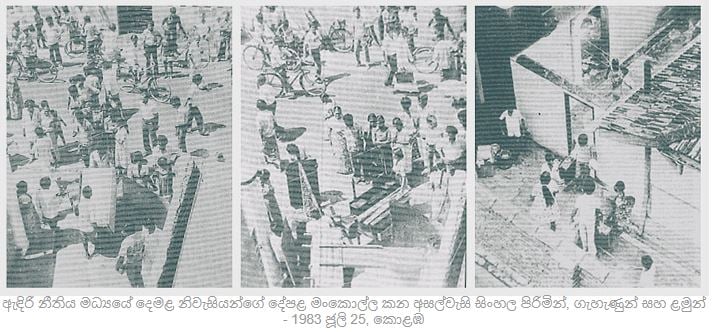

On 25 July 1983, 35 Tamil political prisoners housed in the Chapel Ward on the ground floor of Welikada Prison were forcibly removed from their cells and savagely beaten to death using sticks, clubs, iron rods, and other weapons. Two days later, on 27 July, an additional 18 Tamil inmates were killed in similar fashion while prison officials and armed soldiers stood by.

Subsequent investigations revealed that many of the 53 victims had been subjected to extreme torture—limbs broken, eyes gouged out, and their bodies dragged across the open yard in front of the prison.

“My father’s eyes were gouged out while he was still alive. We found out later. He had said he wanted to see Eelam before he died. That’s why they did it,” Madiwannan recounted, his eyes brimming with tears.

The Chapel Ward was divided into four sections—A, B, C, and D—with four corresponding cells on the ground floor: A3, B3, C3, and D3. Cell B3 held six members of the Tamil Eelam Liberation Organisation (TELO), including Selvarajah Yogachandran (Kuttimani), Nadarajah Thangavelu (Thangathurai), and Ganeshanathan Jeganathan (Jegan), who had been sentenced to death following the 1981 Nirveli Bank robbery. All six were in the process of appealing their sentences.

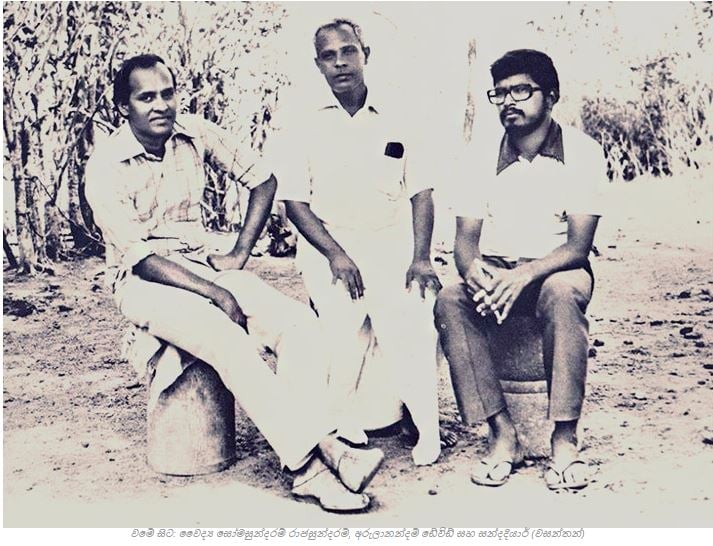

Cell D3 housed 29 Tamils arrested under the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA), while C3 contained another 28. In the juvenile ward, nine more Tamil prisoners were detained, including Dr Dharmalingam, Kovai Mahesan, Dr Somasundaram Rajasundaram, A. David, Nithyanandan, and Catholic priests Fathers Singarayar, Sinnarasa, Jeyathillakaraj, and Dr Jeyakularajah.

The then-Deputy Commissioner of Prisons, Christopher Theodore Jans, confirmed that most inmates in D3 were either suspects or recommended for early release.

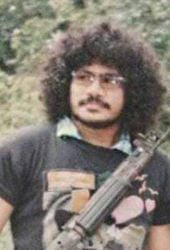

Cell A3, however, was different—it housed what were deemed the most dangerous and escape-prone prisoners, all of whom were Sinhalese. Among them was Sepala Ekanayake, serving a life sentence for the 1982 hijacking of an Alitalia aircraft. Later reports suggest he played a key role in inciting and leading the attack.

Independent reports indicate that prison guards were usually stationed in both the upper and lower levels of the Chapel Ward, with at least 15 officers on duty, especially near the ground-floor corridor. Yet, on the day of the attack—25 July—the number of guards was significantly reduced.

Academics from the University Teachers for Human Rights (UTHR-Jaffna) noted that the anti-Tamil sentiment already brewing outside the prison, especially near Borella cemetery, had found its way inside Welikada. On that day, numerous prisoners from the lower section were inexplicably removed—likely emboldening the Sinhalese inmates. Meanwhile, Tamil prisoners, who received daily newspapers, were aware of the escalating violence in Colombo.

According to reports, between 10 a.m. and 11 a.m., unrest began to emerge within the prison. By around 2 p.m., a large group of Sinhalese inmates approached cell B3, attempting to break open the locks and force entry into cells housing Tamil detainees.

Manikkadasan, a Tamil prisoner in cell C3, witnessed from a nearby window how his fellow inmates, already beaten or dead, were dragged by their limbs across the prison yard by Sinhalese attackers, as guards looked on passively.

A Coordinated Genocide?

The evidence suggests that security arrangements within the prison were deliberately altered. More disturbingly, questions remain about the conduct of the armed military unit stationed at the prison’s main gate.

According to the prison superintendent Leo de Silva’s testimony during a magistrate’s inquiry, he called out for assistance from the soldiers. However, he claimed they were unable to control the sheer number of attacking prisoners.

At the time, over 800 inmates were housed in the two-storey Chapel Ward. De Silva noted that although the military was present and corpses lay scattered in the corridors, no additional troops were deployed to control the situation. It is suspected that the soldiers may have intentionally stood down, allowing the Sinhalese prisoners to carry out their attacks.

This theory gains weight when considering that the anti-Tamil pogrom began with riots near the Borella cemetery, where state-sponsored funerals for 13 soldiers killed in the North were taking place.

Authorities claimed that the military presence at the prison was to prevent Tamil prisoners from escaping. Yet those very prisoners—many of whom were awaiting appeal—were left unprotected. No official explanation has ever been given as to why the military was not called in to prevent the massacre.

The prison was under the watch of a battalion from the 4th Artillery Regiment, commanded by Lieutenant Mahinda Hathurusingha. According to his statement to the magistrate, he had been stationed with 15 soldiers at a nearby military rest house just prior to the attacks. Five soldiers were already positioned at the main gate, with 25 more located approximately 200 metres away.

Lieutenant Hathurusingha claimed that a guard from the main gate alerted him to the violence, prompting him to respond with seven soldiers. He stated that upon their arrival, the attackers immediately retreated.

Lieutenant Hathurusingha’s Role Under Scrutiny

Independent investigators have cast serious doubt on the credibility of the statement given by Lieutenant Mahinda Hathurusingha regarding the 1983 Welikada Prison massacre. According to the University Teachers for Human Rights (UTHR – Jaffna), his account does not align with that of Prison Superintendent Leo de Silva. UTHR-Jaffna asserts that based on de Silva’s testimony, there is strong reason to believe the military failed to intervene to stop the Sinhala inmates from attacking their Tamil counterparts.

The soldiers stationed at the prison were armed with Self-Loading Rifles (SLRs), yet, as UTHR points out, they did not fire a single shot to protect the Tamil prisoners. This claim is supported by Suriyah Wickramasinghe, then Secretary of the Civil Rights Movement (CRM), who uncovered through her investigations that the military remained passive throughout the violence, despite being fully armed.

Army Obstruction and Police Denial

Christopher Theodore Jans, then Acting Deputy Commissioner of Prisons, testified at the inquest that he had gone to Borella Police seeking assistance and had informed Deputy Inspector General R. Sundaralingam of the situation. Although a police team eventually arrived at Welikada, Jans stated that the army personnel barred them from entering the prison. He further noted that neither the army nor prison staff provided him with any support to control the crisis.

Suriyah Wickramasinghe emphasised that this constituted a gross violation of the Prisons Ordinance, which states that if prison authorities lose control of a situation, it is their legal duty to summon the police. She also highlighted that the military has no legal right to obstruct such intervention.

Violation of International Humanitarian Law

Despite Jans’ efforts to save the injured prisoners, the army repeatedly blocked him, arguing that the detainees were already dead. Lieutenant Hathurusingha refused to allow any external assistance. Even when Jans telephoned an army major to request that the wounded be taken to hospital, the request was denied. The major insisted that such a transfer required approval from the Secretary of Defence.

Independent experts have described this as a grave violation of international humanitarian law. It is alleged that Lieutenant Hathurusingha deliberately prevented life-saving medical intervention. Investigators further note that, within a military hierarchy, the rank of Deputy Commissioner of Prisons is equivalent to a Major General or a Senior Brigadier—far senior to a lieutenant. It was therefore both irregular and unlawful for a junior officer such as Hathurusingha to obstruct a senior civilian official acting in his duty.

Suriyah Wickramasinghe contends that the actions of the military, particularly under Lieutenant Hathurusingha’s leadership, constitute a direct violation of the UN International Convention on the Rights of Prisoners. She underscored that all detainees, regardless of their alleged crimes or ethnicity, are entitled to medical care and humane treatment. Wickramasinghe also argued that military personnel are not legally bound to await superior orders in matters of humanitarian intervention.

Hence, the senior military and police officers who acted under—or allowed—the leadership of Lieutenant Hathurusingha are accused of not only negligence but complicity in the massacre.

Jans’ Final Attempts at Intervention

In his testimony, Jans recounted that he had escalated the matter to higher military authorities, including Army Commander Tissa Weerasuriya, who had just arrived from Jaffna that same day. However, Commander Weerasuriya too reportedly showed little concern. Jans also contacted Deputy Inspector General Ernest Perera and Inspector General of Police Rudra Rajasingham.

In a final effort, Jans travelled to the National Hospital in Colombo, where he met with the Director, Dr Lucian Jayasuriya, and made arrangements to admit the injured. However, those efforts were ultimately thwarted by the military’s refusal to release the prisoners from custody.

Former Presidential Secretary Bradman Weerakoon later testified that during the critical hours of the massacre, President J.R. Jayewardene, Defence Secretary Colonel C.A. Dharmapala, and other senior government officials were present at Army Headquarters.

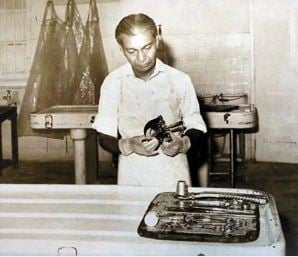

The First Post-Mortem Examination

Within hours of the massacre, the bodies of the 35 murdered prisoners were transferred to the office of the Chief Judicial Medical Officer (JMO) in Colombo for post-mortem examinations. However, Dr M.S. Lakshman Salgado, the JMO at the time, refused to begin the autopsies without a magistrate’s order—a legal requirement in such cases.

Despite this, the police made strenuous efforts to bypass this obligation. In fact, they had failed entirely to request the necessary order from the Chief Magistrate of Colombo, Keerthi Sri Lal Wijewardene. Recognising the gravity of the situation, Dr Salgado personally visited the Magistrate at his residence in Havelock Town to obtain the order—something well beyond his official duties but deemed necessary under the extraordinary circumstances.

Surprisingly, the Magistrate appeared unaware of the massacre. Either he had not been properly informed by the police, or he had chosen to remain uninformed. Despite Dr Salgado’s attempts to explain the urgency, the Magistrate seemed more interested in discussing unrelated topics, such as Colombo’s growing drug problem. He even invited the doctor to join him for tea and sandwiches.

When Dr Salgado finally pressed for the order, the Magistrate responded:

“I will come with you to your office. But to issue a post-mortem order, the police must report the facts to me and submit an official request.”

This interaction confirmed that the police had failed in their legal responsibility.

Eventually, the Magistrate issued the required order following a formal request by Hyde de Silva, the Officer-in-Charge of the Borella Police Crime Branch.

Photographs, Intimidation, and Ethnic Targeting

During the post-mortem, Dr Balachandra, an assistant to the forensic pathologist, took photographs of the corpses. This is a routine and crucial step in murder investigations, as such photographic evidence is essential during legal proceedings. The medical officers who conduct post-mortems are often called as expert witnesses, and visual documentation plays a vital evidentiary role.

However, several members of the forensic office staff, who questioned why Dr Balachandra—a Tamil—was taking the photographs, complained to Deputy Solicitor General Tilak Marapana. They alleged that he was secretly gathering evidence against Sinhalese individuals.

It was only due to the intervention of Dr Salgado—who confirmed to Marapana that he had personally instructed Dr Balachandra to take the photographs—that the Tamil doctor avoided persecution. Without that defence, his fate could easily have mirrored that of the Tamil prisoners who were slain.

Dr Salgado was reportedly wary not only of the future of the inquest but also of his own safety. Some reports suggest he sent the post-mortem findings to Professor Bernard Henry Knight, a leading forensic pathologist, with instructions to publish the results if he were to die under suspicious circumstances.

A Biased and Legally Flawed Inquest

The initial magisterial inquest took place on the evening of 26 July at the Welikada Prison. Present were Magistrate Keerthi Wijewardene, Secretary to the Ministry of Justice Mervin Wijesinghe, Deputy Solicitor General Tilak Marapana, and Senior State Counsel C.R. de Silva, who led the proceedings on behalf of the Attorney General’s Department.

The inquest, however, has been widely criticised for being heavily biased in favour of the state. It failed to uphold the basic legal principle of victim representation. Not one of the 53 murdered prisoners was legally represented, and no relatives were interviewed or allowed to participate in the inquiry.

Most shockingly, no injured Tamil prisoner or eyewitness from among the survivors was summoned to give testimony. According to independent investigators, this omission was not only unlawful but appeared to be a deliberate effort to suppress key evidence and protect those responsible for the massacre.

Silencing the Survivors

The surviving Tamil prisoners were neither allowed to voice the horrors they had endured nor were they granted the opportunity to bear witness. One such survivor, Kandaiah Rajendran (Robert), who had firsthand knowledge of the atrocities, was murdered in the second attack, seemingly to prevent his testimony from ever surfacing. His evidence was not even considered during the initial magisterial inquiry, and his death appears to have been a deliberate act to ensure silence.

Following the massacre, on 27 July, Magistrate Keerthi Wijewardene instructed the police to produce any suspects immediately. However, before this order could be meaningfully executed, Superintendent of Police Hyde de Silva obtained authorisation to dispose of the bodies under Section 15A of the Emergency Laws and Regulations Act. This request was not opposed by Deputy Solicitor General Tilak Marapana. Bound by the Gazette notification, the Magistrate had no legal power to refuse the request, effectively shutting the door to further judicial inquiry—just as the Jayewardene government had intended.

State-Sanctioned Disappearance of Bodies

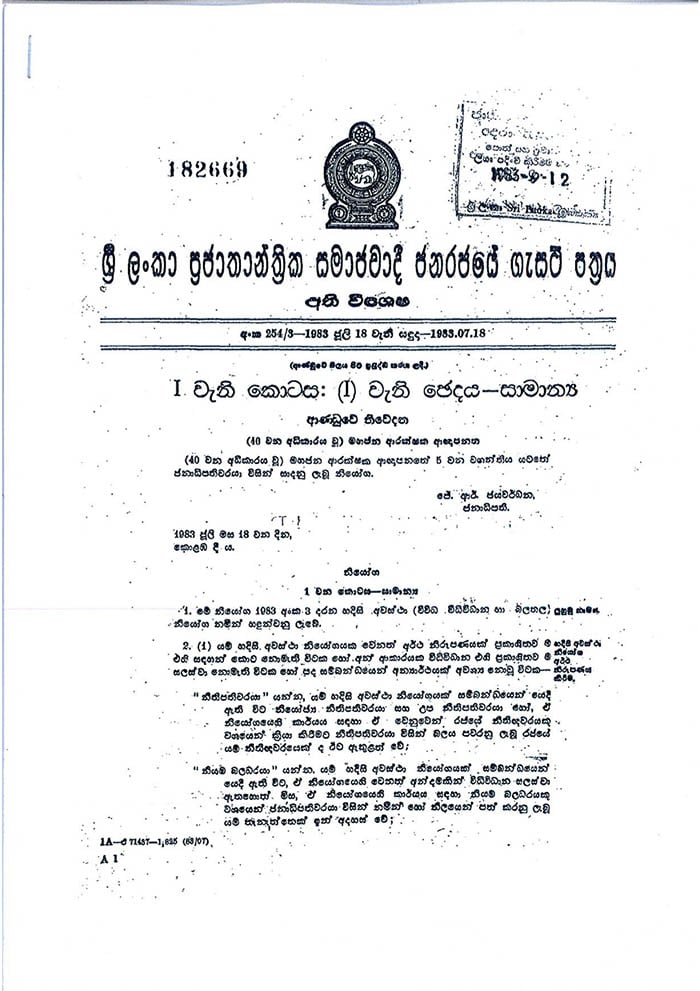

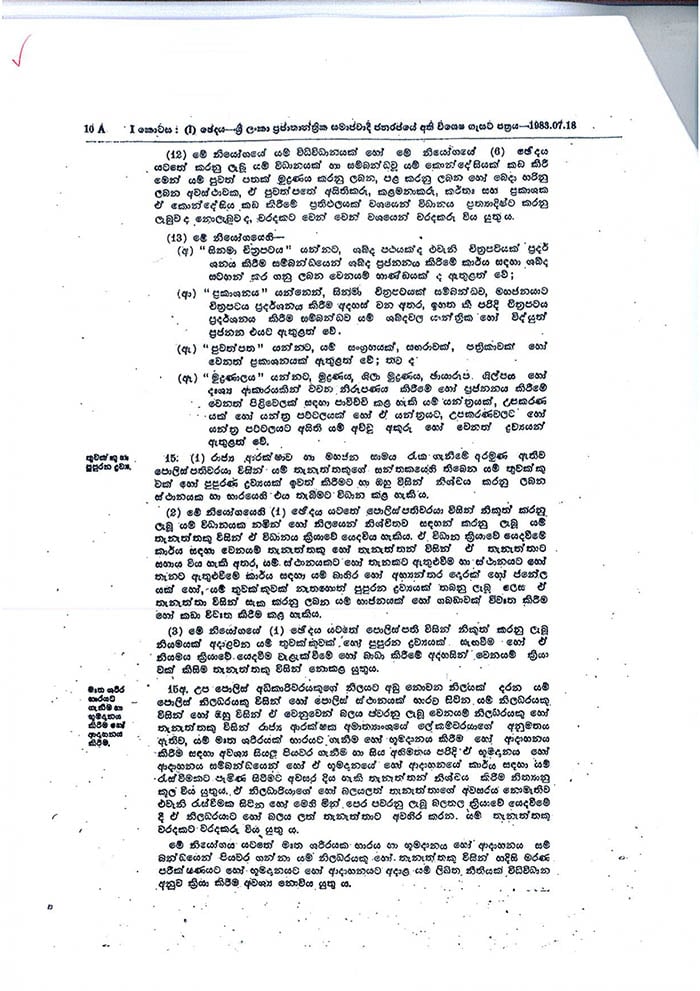

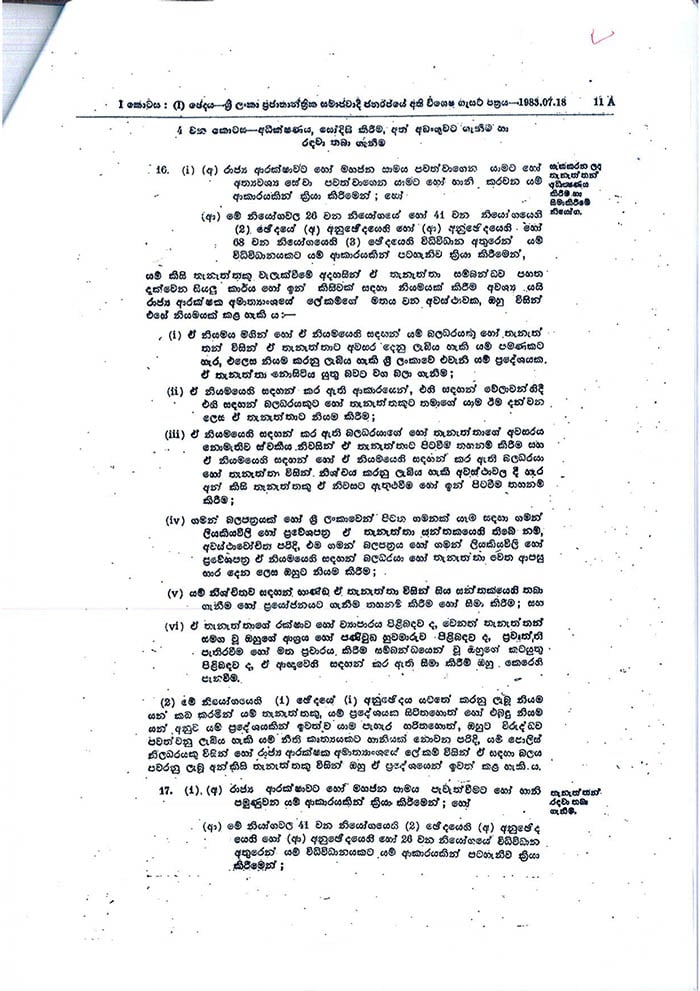

The legal justification for this cover-up lay in Gazette Notification No. 254/03, issued on 18 July 1983, which allowed for the disposal of dead bodies—without post-mortem examination, without returning them to next of kin, and without any judicial or medical investigation. The regulation granted sweeping powers to the executive, overriding the Constitution and criminal law.

Enacted under the Public Security Act, the Gazette allowed an officer not below the rank of Assistant Superintendent of Police to dispose of bodies with the Defence Secretary’s approval. Crucially, it stated that this procedure was not subject to any other law. As a result, the Welikada massacre could be erased not just from public view but from the legal framework altogether.

When the state is empowered to decide what constitutes a crime, without judicial oversight, it dismantles the entire foundation of justice. In this instance, the brutal torture and murder of defenceless prisoners under state custody, with no legal accountability, is the very definition of systemic impunity.

As Madiwannan, the son of murdered Tamil political prisoner Kuttimani, asks poignantly:

“Everyone who was killed was in prison. The government must be held responsible. How can the court say that genocide is not a crime? Then is there no one accountable?”

The Second Massacre: Another Failure of the State

Following the first massacre, the situation both inside and outside the prison was deteriorating rapidly due to widespread anti-Tamil pogroms across the country. Instead of acting decisively to prevent further attacks, the Jayewardene government remained inert. Surviving inmates reported that several prison officers actively incited Sinhalese prisoners, fuelling a volatile and racist atmosphere within Welikada Prison.

Those remaining Tamil prisoners had every reason to fear a second wave of violence. The international community had already condemned the initial killings, and pressure mounted for the protection of the survivors. Deputy Commissioner Jans was summoned to a Security Council meeting at Army Headquarters on 27 July, where he warned Justice Ministry Secretary Mervyn Wijesinghe of an imminent second attack.

Despite having ample time and credible intelligence, the authorities failed to implement any meaningful safety measures. Instead, they allowed history to repeat itself. Although there was initial talk of transferring the survivors to Jaffna Prison, it was later decided to move them to Batticaloa. Tragically, before this transfer could occur, 18 more Tamil prisoners were murdered—this time with direct complicity from the prison authorities.

Second Inquest: A Repeat of Injustice

Before the victims’ blood had even dried, Justice Secretary Mervyn Wijesinghe called for a second magisterial inquiry. Once again, Tilak Marapana and C. R. de Silva led the proceedings on behalf of the Attorney General’s Department, and once again, no legal representation was given to the victims.

Evidence presented at the second inquest further confirmed that authorities had prior knowledge of the potential for violence. Chief Jailor W\.M. Karunaratne admitted he had received intelligence about the risk of another attack and had informed Jans. Yet, the prisoners under the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) were consistently labelled as “terrorists”, suggesting that the state saw them as less deserving of protection than their Sinhalese attackers. This language served not only to justify the killings but to dehumanise the victims.

Mass Burial: From Prison to Pit

The bodies of the murdered prisoners were wrapped in white cloth and loaded onto army trucks. Deputy Commissioner Jans witnessed this. The prison doctor, Perinpanayagam, confirmed their deaths before the bodies were transported to the Borella public cemetery.

There, in a remote corner of the graveyard, a pit was dug. Under heavy police and army presence, the bodies were cremated—presumably to destroy any forensic evidence. However, as history shows, evidence of atrocity is not so easily erased. It lives on in documents, memories, eyewitness accounts, and in the conscience of a nation.

Eyewitnesses, such as Anees Thuwan, a municipal worker at the cemetery, later described how two army trucks arrived with 35 blood-soaked bodies, followed by 18 more the next day. He recounted how a soldier operating an earth-moving vehicle dug a large pit in the middle of the night, allegedly under orders from senior officials. The cemetery’s caretaker had reported the incident, but the then Mayor of Colombo, Ratnasiri Rajapaksa, instructed that the army be allowed to proceed.

It remains unclear whether this testimony, or that of the cemetery officials, was ever examined in court.

A Demand for International Justice

Despite the regime’s best efforts to bury the truth, relatives of the victims and survivors continue to demand justice. Former MP M.K. Sivajilingam has called for a transparent and independent investigation, preferably with the involvement of international experts, stating:

“We know where they were buried. The government and the Colombo Municipal Council are now one. They can open an investigation. What we need is truth and justice.”

These demands stem from a deep mistrust in the Sinhala-dominated state machinery, which failed to deliver justice not just for Welikada, but for decades of atrocities targeting Tamil detainees.

As Madiwannan, Kuttimani’s son, stated in anguish:

“We cannot expect justice from the Sinhala rulers. But at least tell us where our loved ones were killed and buried or burned. Let us light a candle and leave flowers.”

State Criminality and the Erosion of Justice

While the Jayewardene government suppressed the massacre, civil society activists, including Suriya Wickramasinghe, managed to file 35 court cases with the support of surviving witnesses. This proves that even decades later, justice is possible—if the will exists.

The Welikada massacre was no accident. It was a premeditated act of mass violence, involving not just individual prisoners but state officials, prison authorities, police, military officers, and the executive leadership. Among them was Deputy Solicitor General Tilak Marapana, who went on to become Attorney General and later served as Minister of Defence and Minister of Law and Order—roles through which he continued to wield considerable influence over the very system he helped to shield from scrutiny.

This revolving door between state crimes and political promotions illustrates the entrenched culture of impunity. At the time, key figures in law enforcement and prosecution, such as IGP Rudra Rajasingham, DIG Sundaralingam, and Attorney General Siva Pasupathi, were themselves Tamil. Yet, their positions proved ineffective against the Sinhala state’s political and military machine. Their presence did not translate into justice.

Beyond Welikada: A Pattern of Impunity

The Welikada massacre is not an isolated incident. It is part of a broader pattern of state-enabled prison killings targeting Tamils:

* 1997 – Attack on Tamil prisoners in Kalutara Prison.

* 2000 – Bidhunuwewa Youth Rehabilitation Centre: 26 Tamil youths murdered by Sinhalese villagers while in custody.

* 2012 – Political prisoners Ganeshan Nimalaruban and Mariyadas Del Rukshan were tortured and killed in Vavuniya Prison.

None of these atrocities have seen justice. In the Bidhunuwewa case, all accused officials were acquitted. In 2012, a fundamental rights petition filed by Nimalaruban’s mother was dismissed by then Chief Justice Mohan Peiris, who stated that the case was politically motivated and that relatives of “terrorists” were abusing the legal system to seek asylum abroad. Gotabhaya Rajapaksa later appointed him as Sri Lanka’s Permanent Representative to the UN—a move seen by many as a reward for his loyalty to the Rajapaksa regime, and his position had sustained for another eight months, under the current National Peoples Power reigme.

“Justice Demands More Than Ashes”

Madiwannan, with a voice trembling from loss, concluded:

“We are ready to give our blood, our bones, our very flesh to uncover the truth about our fathers, brothers, and friends. But we know the Sinhala government will never give us justice. Just tell us where they were burned. Let us mourn them with dignity.”

*Adapted from original article by Independent Journalist K. Wijesinghe.