By Roger Srivasan

Introduction

I was born in the Northern part of Sri Lanka, but my childhood and much of my life unfolded in the United Kingdom. For half a century I have lived in a society where the environment has steadily been pushed higher up the public agenda. I remember vividly the day the UK government, following Wales, Northern Ireland, and Scotland, decided to charge for plastic carrier bags. What seemed like a small 5-pence nudge at the till quickly transformed public behaviour. Within a few years, plastic bags on UK beaches had fallen by 80 per cent. Now Sri Lanka is embarking on a similar journey, banning single-use carrier bags. The instinct is right.

The question is: can we replicate the British success story, or will our own economic and social realities blunt the impact?

What Britain Did Right

The UK’s approach was gradual and carefully staged. Wales led the way in October 2011 with a 5p levy.

Northern Ireland followed in 2013, Scotland in 2014, and England in 2015. By 2021, the charge doubled to 10p and was extended to all retailers. The results were dramatic: fewer plastic bags in circulation, cleaner beaches, and a shift in mindset. Why did it work so smoothly? Three factors mattered:

1. Cars and convenience – most shoppers drove, storing “bags for life” in their car boots.

2. Alternatives at scale – supermarkets offered reusable options, reminders at tills, and visible messaging.

3. Affluence and awareness– the public could absorb a small fee and embraced the environmental argument. In short, Britain harnessed small incentives to achieve a big cultural change.

Europe: Levy or Ban

The EU acted through Directive 2015/720, requiring member states to cut consumption of lightweight carrier bags. Some chose levies, others bans. Ireland pioneered the levy in 2002, slashing usage almost overnight.

France phased in bans in 2016–2017. Germany introduced a nationwide ban on lightweight bags from 2022.

The lesson? Whether by fee or outright prohibition, the direction is unmistakable: fewer disposables, more re-use.

The Anglosphere Experience

Across the English-speaking world, the pattern is varied but unmistakable. – United States: With no federal law, individual states took the lead. California, New York, New Jersey, Washington, Oregon, Maine, Vermont, Connecticut, Delaware, Colorado, and Rhode Island now restrict or ban bags. California goes further: from 2026 all plastic grocery bags, even thick “reusables,” will be outlawed. – Canada: The federal government introduced a ban in 2022, now under legal challenge. A court stay keeps the rules in effect while the appeal proceeds. – Australia: Every state and territory has banned lightweight plastic bags. Some, like South Australia, are widening restrictions to cover more single-use plastics.

Why Sri Lanka Is Different

Sri Lanka faces unique obstacles. The average household here does not mirror the British suburban shopper with a car boot full of sturdy bags. Many rely on buses, trains, three-wheelers, or walking. Carrying groceries in heavy reusable bags is a far greater inconvenience. Economic constraints deepen the dilemma. A reusable cloth or jute bag costs more than a flimsy polythene one. For lower-income families, even small costs bite hard. Meanwhile, our retail landscape is fragmented: modern supermarkets, wet markets, and thousands of kades. Enforcing a uniform ban across this patchwork is daunting.

The Case for Action

Yet the environmental argument is overwhelming:

– Urban flooding: Blocked drains choked with polythene make monsoon deluges more destructive.

– Health: Burning discarded plastic releases toxic fumes in residential areas.

– Tourism and coasts: Marine litter damages fisheries and our international image. We cannot afford inaction. But we must tailor solutions to our realities.

A Sri Lankan Way Forward

If Sri Lanka is to succeed, the ban cannot stand alone. It must be paired with innovation and practicality:

1.Start with a charge, then escalate – follow the UK’s path, giving people time to adapt.

2. Subsidise reusable bags – make cloth or jute carriers cheap, or free at the start, especially for low-income households.

3. Baglibraries and rentals – supermarkets and kades could lend bags for a deposit, refundable on return.

4.Foldable pocket bags – sell compact cloth bags at bus stands and railway kiosks.

5. Market-specific solutions– for wet markets, reusable crates or woven sacks rented out per trip.

6. Unified enforcement – clear, simple rules for supermarkets and kades to avoid confusion or unfair penalties.

Conclusion: Worthy, but Adapted

The ban on plastic bags is a worthy initiative. It signals responsibility, protects our environment, and reminds us that small choices carry large consequences. But Sri Lanka must adapt the model. We cannot simply import the UK approach and expect identical results. In Britain, affluence, car culture, and retail centralisation smoothed the path. Here, success will depend on education, affordability, and localised alternatives. If we design the transition wisely, Sri Lanka can reap the same environmental rewards without burdening its people. The lesson is clear: ban the bag, but bend the policy to Sri Lankan realities.

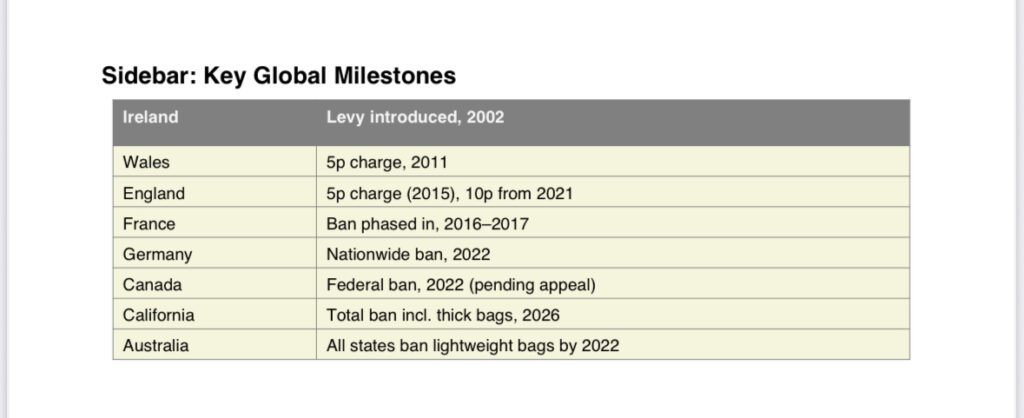

Sidebar: Key Global Milestones