By Adolf

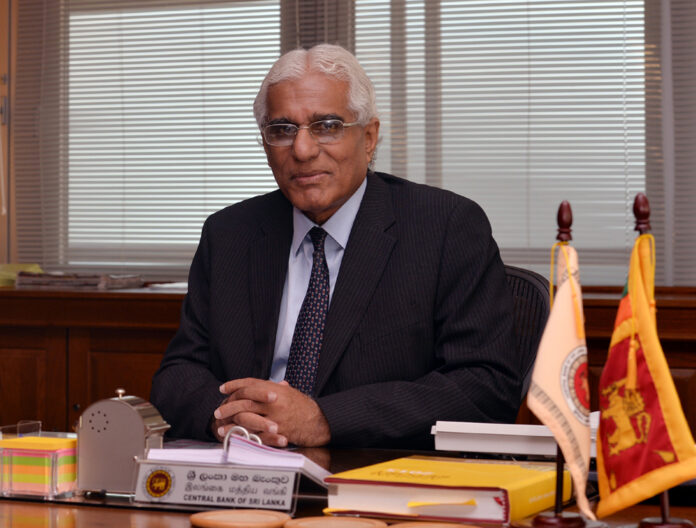

Sri Lanka’s economic meltdown in 2022 did not happen overnight. It was the result of a series of decisions—short-sighted, politically expedient, and economically reckless—that left the country dangerously exposed to global capital markets. Chief among them was the Central Bank’s policy of aggressive commercial borrowing between 2015 and 2019, under successive administrations, and most significantly, during the tenure of Dr. Indrajith Coomaraswamy as Governor.

Between 2015 and 2019, Sri Lanka issued seven International Sovereign Bonds (ISBs) amounting to nearly USD 10 billion, at interest rates ranging between 5.5% and 8.9%. The timeline tells its own story:

• 27 Oct 2015 – USD 1.5 billion (10-year)

• 11 July 2016 – USD 500 million (~5.5-year)

• 18 July 2016 – USD 1 billion (10-year)

• 11 May 2017 – USD 1.5 billion (10-year)

• 18 April 2018 – USD 1.25 billion (10-year)

• 7 March 2019 – USD 2.4 billion (5-year + 10-year tranches)

• 24 June 2019 – USD 2 billion (5-year + 10-year tranches)

In less than five years, the country’s external commercial debt stock ballooned from USD 5 billion to over USD 15 billion, while the maturity profile shortened dangerously. In essence, Sri Lanka borrowed short-term, high-cost money to fund long-term fiscal gaps and recurrent expenditure.

These borrowings were often defended by the Central Bank as part of “liability management exercises” — a euphemism for rolling over maturing debt with fresh, more expensive loans. The claim was that refinancing would “smoothen the maturity profile.” In reality, it merely postponed the crisis, piling up obligations on future governments while doing little to strengthen reserves or expand export capacity.

By the time the bond spree ended in 2019, Sri Lanka’s external debt service obligations exceeded USD 4 billion per year, while annual export earnings hovered around USD 11 billion. This mismatch was unsustainable. The foreign reserves, which stood at USD 8.2 billion in 2014, fell to USD 7.6 billion by end-2019 — despite billions borrowed.

The real tragedy was that none of these funds were directed toward growth-enhancing investments. Instead, they were used to prop up the rupee, fund public sector salaries, and pay off older loans. The government’s failure to pursue fiscal reforms — especially broadening the tax base and curbing subsidies — meant the country was trapped in a vicious cycle of debt rollover.

Dr. Coomaraswamy, while respected for his professionalism, also conferred Deshamanaya by President Sirisena , presided over one of the most imprudent borrowing phases in post-independence history. His administration failed to challenge the Treasury’s excessive appetite for external debt, even when the macro fundamentals did not justify it. The result was a debt profile heavily tilted toward commercial borrowings, with over 50% of foreign debt in ISBs by 2019 — a level of exposure that would later prove fatal.

When the COVID-19 pandemic struck and global markets tightened, Sri Lanka’s access to refinancing vanished overnight. With no fallback reserves and no IMF arrangement in place, default was inevitable. The first missed ISB payment in April 2022 marked the country’s first-ever sovereign default since independence — a direct consequence of the 2015–2019 borrowing binge.

In hindsight, the Central Bank’s strategy under Indrajith and his successors was fundamentally flawed on three counts:

1. Overreliance on commercial debt: Instead of mobilising cheaper, long-term concessional financing from multilaterals and bilateral partners, Sri Lanka chose to rely on volatile capital markets.

2. Poor debt management coordination: The Central Bank and Treasury operated in silos, with little medium-term fiscal strategy to manage repayment risk.

3. Lack of accountability: Borrowings were presented as “routine” or “market-friendly,” without adequate parliamentary scrutiny or public disclosure of repayment implications.

The outcome was predictable. By 2020, nearly half of Sri Lanka’s external debt was owed to private creditors, leaving the country with little room to negotiate or restructure quickly. The steep depreciation of the rupee, soaring inflation, and collapse in investor confidence were all symptoms of the same underlying disease: fiscal indiscipline compounded by monetary complacency.

The painful lessons of this period must not be lost on policymakers. Sri Lanka cannot afford to repeat the mistakes of 2015–2019 — where technocratic convenience and political expedience replaced prudent economic judgment. The Central Bank’s independence must be matched by accountability, and every dollar borrowed must be linked to measurable economic outcomes.

If there is one truth the bankruptcy laid bare, it is this: a nation cannot borrow its way to prosperity. Borrowing, when not anchored to reform, only delays the reckoning. Sri Lanka’s road to recovery must therefore begin not with more loans, but with institutional discipline, transparency, and a commitment to live within its means.