In countries like Sri Lanka, with a history stretching back millennia, the true bedrock of social stability and order lies in the unpaid, pervasive service of its religious leaders

The reality is that a significant volume of wrongdoing, including crimes against women and children and endemic minor corruption, remains stubbornly unreported

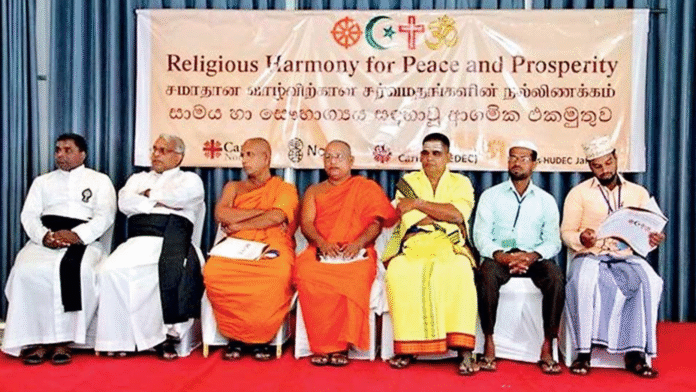

Religious leaders, be they Buddhist monks (Bhikkhus), Hindu priests (Kurukkals), Islamic clergy (Ulama), or Christian pastors, are widely respected figures of integrity and moral authority

In the complex tapestry of modern nation-states, governance is often viewed through the narrow lens of policy, legislation, and enforcement agencies. Yet, in countries like Sri Lanka, with a history stretching back millennia, the true bedrock of social stability and order lies not in the paid bureaucracy, but in the unpaid, pervasive service of its religious leaders. This extensive, voluntary network of moral guidance spanning Buddhist, Hindu, Islamic, and Christian faiths acts as a critical, unpriced pillar that keeps the social fabric whole, preventing a descent into unmanageable crime that no government treasury could ever afford to police.

The sheer scale of this contribution is illuminated when juxtaposed with the nation’s crime statistics. With a population of approximately 21.8 million, the Department of Census and Statistics records the annual grave crimes (homicide, rape, robbery) in 2023 at 44,939, While this figure, and the incarceration rate (which shows only about 0.17% of the population currently in jail), might suggest a relatively low level of overt criminality, it is a profoundly misleading measure. The reality is that a significant volume of wrongdoing, including crimes against women and children and endemic minor corruption, remains stubbornly unreported. Furthermore, as per Department of Prison, in 2024 convicted admission numbers indicated as 47783 and un-convicted as 135550. This statistics suggests that the majority of the prison population comprises of unconvicted individuals awaiting trial, pointing to a justice system struggling with its caseload. In this context of stretched resources and hidden societal ills, the vast majority of the population the 99% who are not incarcerated and who do not feature in crime reports are held in check by a force far older and subtler than the penal code: the fear and habit of moral righteousness instilled by their religious teachings.

The Middle Path as the Core of Social Contract Sri Lanka’s identity is inextricably linked to its religious heritage, dating back over 2,500 years with the introduction of Buddhism. This historical link is not a mere cultural footnote; it is the source code for the nation’s behavioral norms. The central philosophy of Buddhism, the Middle Path and the principle of non-violence (Ahimsa) has seeped into the collective consciousness of the island. These principles form an unwritten social contract that guides the actions of the majority, promoting forbearance, compassion, and ethical conduct.

This influence extends even to the highest levels of statecraft. The nation’s historical commitment to a non-aligned foreign policy being friendly with everyone and maintaining enmity with none is a direct derivation of the Buddhist central path: a preference for neutrality and peace over conflict. It demonstrates that the core religious philosophy shapes not just individual behaviour but also national character and external relations. To suggest that Sri Lanka could simply adopt a purely secular, fear-based legal system, such as those that employ draconian measures common in some Middle Eastern countries, is to ignore this profound historical and cultural depth. Such a path is neither practical nor possible for a country whose very livelihood, tradition, and worldview are organically linked to its long-held religious identity.

The forgotten factor: Proactive prevention vs. reactive punishment

The most “forgotten factor” in evaluating national security and stability is the proactive, preventative discipline exerted by religious institutions. Every Sunday School (Dahama Pasala), every Katib sermon, every kovil gathering, and every church service is, in effect, a massive, free-of-charge public ethics program. However, it is important to state that the government should monitor and prevent Religious extremism and related teaching which is endangering National security and National unity.

Religious leaders, be they Buddhist monks (Bhikkhus), Hindu priests (Kurukkals), Islamic clergy (Ulama), or Christian pastors, are widely respected figures of integrity and moral authority. They are often the first point of contact for individuals grappling with economic distress, addiction, marital conflict, or moral temptation.

They provide:

Moral Policing: They teach the principles (e.g., the Pancha Sila in Buddhism, the Ten Commandments in Christianity, the Five Pillars in Islam) that act as an internal moral compass, stopping wrong deeds before they translate into criminal action.

Community Cohesion: Religious centers serve as vital social support networks, fostering community cohesion (Grama Niladhari regions and local welfare societies often work hand-in-hand with temples/churches) and acting as deterrents against crime by making individuals accountable to a defined community.

Conflict Resolution: They often mediate minor disputes and disagreements at the community level, preventing them from escalating into the grave crimes that burden the formal judicial system.

Those who primarily commit crimes are often those who have either rejected or become estranged from these religious and moral teachings. The state then spends taxpayer money to fund the police, courts, and prisons to punish these individuals, a reactive, highly expensive process. If the proactive deterrence provided by the religious sector were to vanish, the already strained judicial and law enforcement system would be immediately overwhelmed.

The cost of a country without conscience

To imagine a country without religion is to imagine the sudden removal of this universal, unpaid ethical scaffolding. If the current grave crime rate of approximately 45,000 cases per year were to merely double, the state would find its administration rapidly paralysed. The resultant breakdown of social trust, the explosion in police and judicial workload, and the soaring costs of incarceration would make effective governance and the maintenance of the rule of law virtually impossible.

Peace and harmony are not accidents of nature; they are the result of constant, conscious investment in human values. In Sri Lanka, the religious sector represents the single largest, most effective, and least costly source of this investment.

A call for Government partnership

The unpaid service of religious leaders in Sri Lanka is not merely a charitable endeavor; it is an essential public service that provides a foundational layer of social security and order upon which the state can function.

For any government to successfully maintain its administration, ensure security, and pursue economic prosperity, it must formally recognize this contribution. The government’s duty should not be to control the religious domain, but to support and empower it.

This support should manifest through:

Logistical Aid: Providing infrastructure, access to remote communities, and logistical assistance for religious led social work and educational programs like the Dahama Pasalas.

Collaborative Initiatives: Partnering with inter-faith organizations on national campaigns against drug abuse, corruption, and gender based violence, leveraging the moral authority of the clergy.

Financial Support (Where Appropriate): Granting assistance not for worship, but specifically for recognized social service, welfare, and community engagement projects that demonstrably improve social cohesion and ethical conduct.

By giving their fullest support to the religious institutions that discipline the majority and direct them toward good deeds, the government is not being benevolent; it is making the most crucial, cost effective investment in its own survival, stability, and the long term prosperity of the Sri Lankan people. The true rate of “wrongdoing” is kept low not by the size of the police force, but by the profound and enduring influence of the religious path, and the unwavering, unpriced service of its spiritual shepherds.

Aspiring PhD students are encouraged to select this topic for reading, given its substantial National and international positive impact to the society.

The concept of the invaluable social discipline rendered by Sri Lanka’s religious leaders originated with Venerable Halmillewe Saddhatissa Sthavira Monastery in Sacred City, Venerable Vice Incumbent Thero of North Central District, who shared the idea with me, and he should be recognized for it.

(The writer is a battle hardened Infantry Officer who served the Sri Lanka Army for over 36 years, dedicating 20 of those to active combat. In addition to his military service, Dr Perera is a respected International Researcher and Writer, having authored more than 200 research articles and 16 books. He holds a PhD in economics and is an entrepreneur and International Analyst specialising in National Security, economics and politics. He can be reached at [email protected])