By: Isuru Parakrama

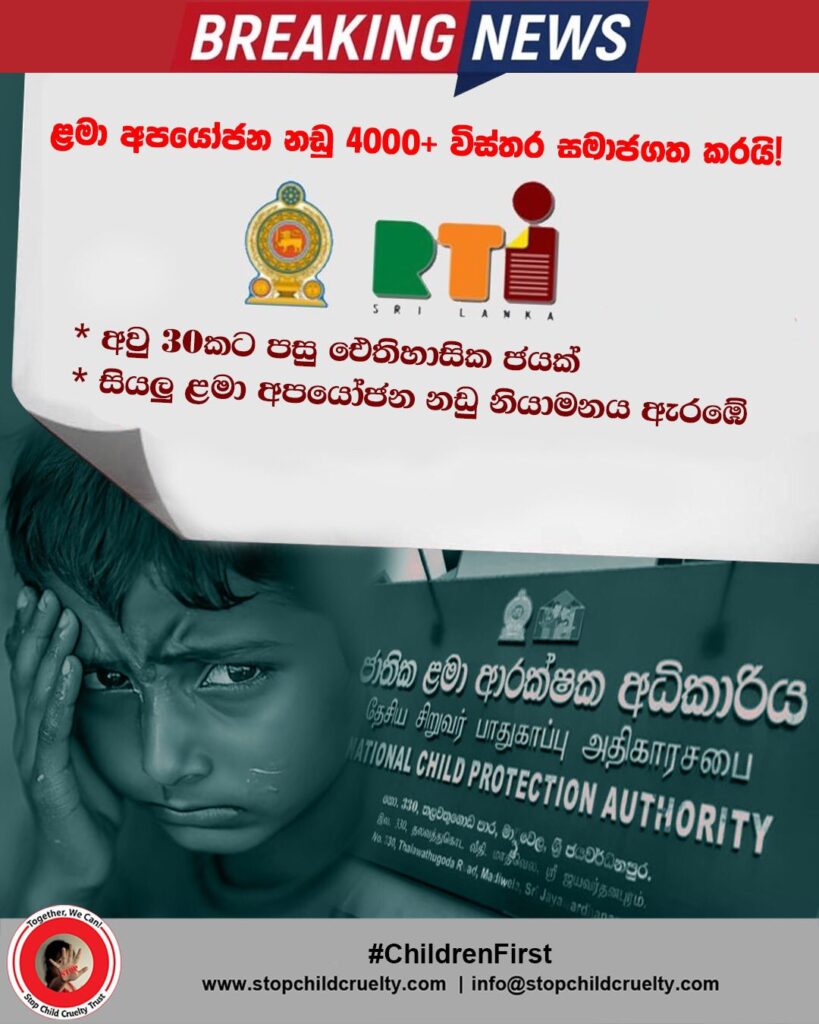

January 24, Colombo (LNW): Passing three decades of institutional silence and suffering much frustration along the way, Sri Lanka has finally taken a historic—if long overdue—step towards accountability in cases of child abuse. For the first time, detailed information on child abuse cases pending before High Courts across the island has been made available to the public, following a directive issued by the Right to Information Commission to the National Child Protection Authority (NCPA).

This disclosure marks a rare victory for transparency in a system that has, for decades, failed the very children it was established to protect.

The National Child Protection Authority was created in 1998 with a clear mandate:

– to prevent child abuse,

– coordinate investigations, and crucially,

– to monitor cases,

as they move through the criminal justice system.

Yet for nearly three decades, there was no comprehensive, publicly accessible mechanism to track what happened to thousands of complaints once they entered police files, the Attorney General’s Department, or the courts. Survivors and their families were left in the dark in agony, with cases being languished for years—sometimes for the entirety of a child’s childhood.

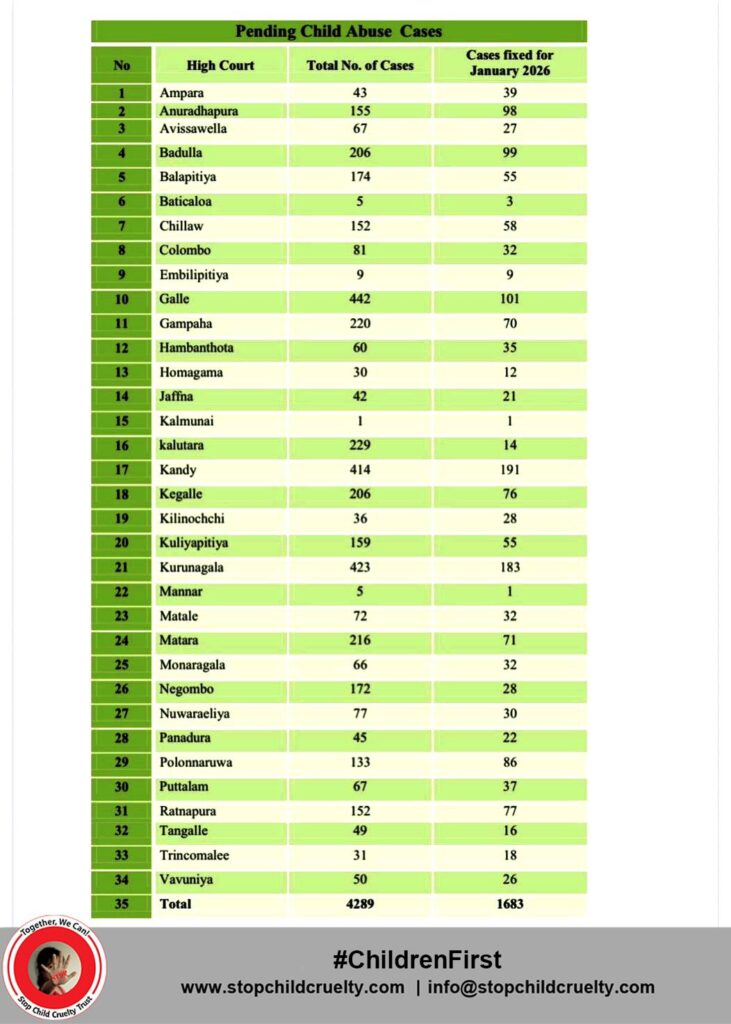

The newly released data exposes the scale of this failure in stark terms. As of January 2026, there are 4,289 child abuse cases pending in High Courts islandwide, with only 1,683 fixed to be taken up during the month.

These are not abstract numbers. They represent children who have waited years for justice, often reliving their trauma at every procedural delay. High Courts in districts such as Galle, Kurunegala, Kandy and Gampaha alone account for hundreds of pending cases each, illustrating how deeply systemic the backlog has become.

Beyond the courts, the picture is even more alarming. Around 40,000 complaints reportedly remain backlogged at the NCPA, while more than 4,000 cases await action at the Attorney General’s Department. Each stage of delay compounds the harm: evidence weakens, witnesses lose hope, and perpetrators remain free. In effect, delay itself becomes a form of injustice, signalling to victims that their suffering is negotiable, postponable, and ultimately expendable.

The cases covered by the disclosed data span some of the gravest offences in Sri Lankan law, including rape, incest, grave sexual abuse, trafficking, cruelty to children and sexual exploitation, all defined under multiple sections of the Penal Code when committed against a person under the age of eighteen.

These are not minor procedural matters but crimes that leave lifelong scars. Justice delayed in such cases is not merely justice denied; it actively undermines a child’s chance to heal and rebuild.

That it took a directive under the Right to Information Act of 2016 to compel this disclosure raises serious questions about institutional accountability. Transparency was not offered voluntarily; it was forced. This suggests that the problem is not a lack of laws or agencies, but a lack of political will and administrative urgency. The NCPA, despite its mandate, failed to establish a proper monitoring system until legally instructed to do so, a failure that must now be acknowledged openly rather than quietly excused.

Yet even amid justified anger, this moment matters. Public access to this data changes the balance of power. Civil society, journalists, lawyers and citizens can now scrutinise patterns, identify chronic delays, and demand explanations. Numbers that were once buried in filing cabinets are now part of the public record, making denial harder and reform unavoidable.

However, transparency alone is not justice. Publishing statistics will mean little unless it is followed by concrete action: strengthening child-friendly court procedures, increasing judicial capacity, prioritising child abuse cases, and holding institutions accountable for negligence. Survivors do not need sympathy statements; they need timely trials, effective prosecutions and a system that believes them.

This disclosure should therefore be understood not as the end of a struggle, but as the beginning of a reckoning. Sri Lanka’s children deserve more than promises and press releases. They deserve equality before the law, justice without delay, and hope grounded in action rather than rhetoric. After thirty years, the truth is finally visible. What happens next will determine whether this historic moment becomes a turning point—or just another missed chance.