Delhi: Billionaire investor Chamath Palihapitiya’s life is meant to be a movie — a rags-to-riches saga from his early childhood in Sri Lanka, to hard-scrabble poverty as a ‘refugee’ in Canada, and then on to Silicon Valley stardom, and mega bucks.

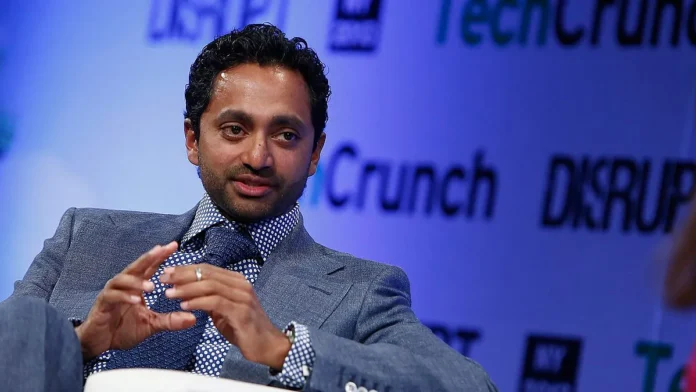

Or perhaps it could be a corporate drama showcasing the 45-year-old’s meteoric ascent at Facebook despite early failures, lucrative and then not-so-lucrative Wall Street gambles, a fluctuating reputation, and expletive-laden wisecracks. If he played himself, he could flaunt his ripped abs on screen, rather than just on Twitter for his 1.5 million followers.

Whether he’s going up or down, Palihapitiya has a polarising effect on his audiences, which he constantly seeks out on social media to promote himself and dole out wise dispensations on life, love, and how to get The Money. Some fans think he should run for Governor of Californiaor even President of the USA — although as a naturalised citizen who wasn’t born there, he’s ineligible for the presidency, just like Arnold Schwarzenegger. Critics, however, dismiss him as a snake oil salesman, a purveyor of dodgy get-rich-easy schemes.

Until a few months ago, Palihapitiya was relentlessly peddling the money-making power of special-purpose acquisition companies (SPACs) — shell entities that raise funds in initial public offerings (IPOs) with the aim of acquiring companies in a sector.

The idea is that the heavily funded shell company will get on board an operational firm with a product that will benefit from merging with the SPAC to then become a listed company in a jiffy. If such an acquisition doesn’t happen, funds need to be returned to investors.

Palihapitiya has a convincing style. He’s a man who speaks with his whole being, bug-eyed with excitement, fingers splayed out, his accent very occasionally lapsing into sing-song Sri Lankanness. He is sure he’ll be the next Warren Buffet — rich enough to mould the world to his liking (“without capital, you’re irrelevant” he has said more than once).

Like Buffet, he brims with advice, but with more comedic flair, surprisingly vulnerable asides about his dysfunctional childhood and dealing with the imposter syndrome, and a peppering of F-bombs.

Of late, though, Palihapitiya has been under a cloud. SPACs saw a boom in valuations in 2020 and 2021, but right now things don’t look so hot. The bubble has burst, reports say.

The stock prices of SPACs were down in general as the frenzy around them fizzled and five Chamath Palihapitiya SPACs that merged with other companies were trading below the starting price of US$10, it was reported in August.

A few months before, in February, Palihapitiya had stepped down from the board of Virgin Galactic, which his SPAC platform, Social Capital Hedosophia, had taken public. He and Virgin Galactic co-founder Richard Branson both faced an investor lawsuit soon afterwards for allegedly covering up flaws in spacecraft and making money by dumping shares.

In 2012, Bloomberg had extolled Palihapitiya and his investors as a “league of extraordinarily rich gentlemen” who were making money and also saving the world.

In August 2022, the same publication pooh-poohed him and his “shrivelling empire”. “The SPAC king has gone silent”, the headline said.

But maybe it spoke too soon.

Days after Bloomberg’s dismal take on his SPACs, Palihapitiya tweeted that one of his SPACs has merged with a digital medicine company.

Fans and detractors had plenty to say in the comments, ranging from “ready to load up my bags for you, king” to “the scammer is back”.

But, either way, the man is risk-on. And for many South Asians, he remains an aspirational “brown brother from another mother” who beat odds like his “unpronounceable” name —“Chamath Phlaplaitlatlalyaysas or whatever…”— to make it big in the west.

Humble, ‘dysfunctional’ beginnings

If you want to understand Chamath Palihapitiya, go through the books he recommends. One of them is Adult Children of Alcoholics by Janet Geringer Woititz, a self-help book about growing up with emotional scars wrought by a substance-abusing parent. In this case it was Palihapitiya’s now-deceased father, Gamage.

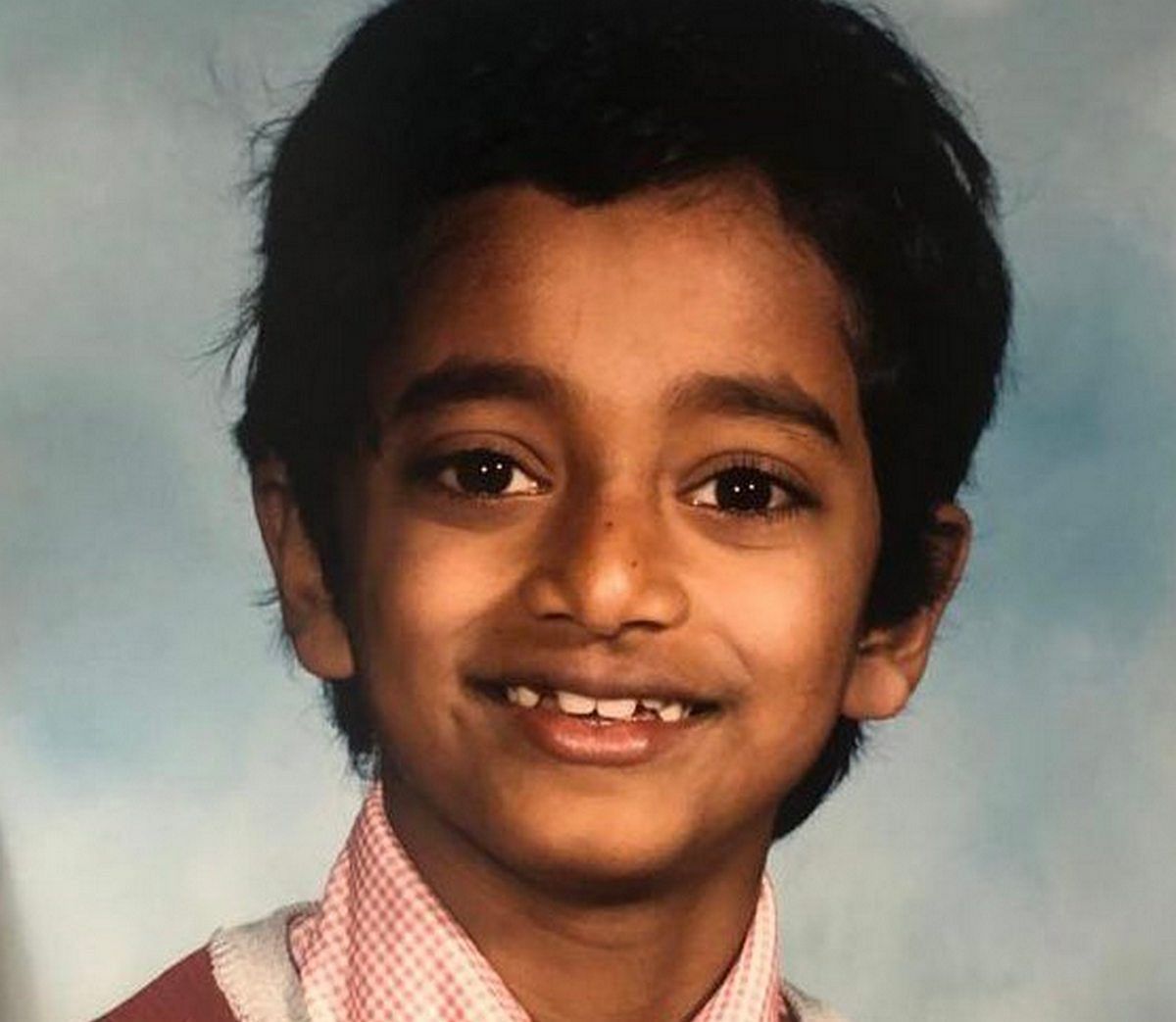

Palihapitiya was born in Sri Lanka in 1976, and moved to Canada with his family at the age of five when his civil servant father was posted to the Sri Lankan High Commission in Ottawa.

When the posting ended in 1986, his father applied for refugee status and stayed back to give his children a better education, and also because he thought he’d be killed by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE).

But life in Canada wasn’t easy. His father was unemployed for long periods of time and money was tight.

“I grew up in a very kind of dysfunctional household on welfare. And that compounded a bunch of shit in my life that was not great. We were very focussed on money. It was a huge point of pressure and tension in the family. It created massive depression in my father, drinking. Just, it was very dysfunctional,” Palihapitiya said at a 2017 chat at Stanford University.

A clue to how Palihapitiya overcame these odds is on another book he recommends: René Girard’s Mimetic Theory by Wolfgang Palaver. According to Palihapitiya, “the idea is that you’re born without preferences and you kind of just copy what’s around you”.

It’s an idea he elaborated upon in the Stanford conversation: “I just copied… a lot of my life, quite honestly, is just copying the things that I see…Be around high-functioning, high-quality people and just copy the shit that they do. Observe the shit that’s kind of crappy and then don’t do that stuff. It’s not a fucking complicated formula.”

It’s clearly something Palihapitiya has given much thought too, especially in view of another recommended read: The Great Mental Models: General Thinking Concepts by Shane Parrish, which sets out nine mental models to fashion better decision-making by emulating greats like Socrates.

For Palihapitiya, who managed to earn a degree in electrical engineering despite financial constraints, a major role model was tech magnate Terry Matthews. The young Palihapitiya held one of his first jobs at Matthews’ organisation Newbridge Networks in Ottawa, as an IT help desk worker.

“He was a billionaire. And I was like, what the fuck is that word?…this guy was risk on. And I was like, I want to be this guy. I want to be this mega-compounder, swashbuckling around, trying to do really cool shit in the world”, he said at Stanford.

Above all, in Palihapitiya’s book recommendations, you see his intense desire for money, power, winning, and admiration for intelligence and cunning. For instance, there’s Michael Lewis’ Liar’s Poker, a riveting read with bits about Wall Street’s biggest bond traders wagering millions of dollars on poker.

Palihapitiya himself is a poker player who has collected over 100,000 dollars in poker earnings.

But that, of course, isn’t the only way he managed to earn hundreds of millions by his early 30s.

A money-maker for Facebook

In the early 2000s, Palihapitiya decided to follow his girlfriend and future wife Brigette Lau (they divorced in 2018) to California, where he excelled at AOL and then followed it up with his first venture capital at Mayfield Fund.

But the big break, as it were, came when a struggling startup founder called Mark Zuckerberg, whom he’d met while exploring a tie-up with AOL Instant Messenger (AIM), offered him a job in 2007.

In his book Facebook: The Inside Story, author and journalist Steven Levy details how Palihapitiya had a less than stellar start at Facebook since he was associated with its controversial purchase-tracking programme, Beacon. Levy writes that even Palihapitiya felt he should be fired, but instead Zuckerberg gave him another chance.

This time, Palihapitiya shone as the ideas and execution guy for how Facebook could grow its monthly active users. During his stint, he was both admired and considered a bully, Levy writes, but the results of his work left no room for doubt.

When Palihapitiya started at Facebook, the platform had under 50 million users, and by the time he left in 2011, the number was 750 million.

The numbers in Palihapitiya’s bank balance were also impressive — Facebook had made him a centimillionaire. In 2011, he set up a VC firm called Social + Capital (later rebranded to Social Capital), which invested in companies like workplace messaging platform Slack.

For seven years, Palihapitiya’s company seemed to be going strong. As he put it in an interview with Vox, he was “a billionaire at 32” and “owned a sports team at 33 or 34”, but he wasn’t “happy” and was going through an “identity crisis”— something that he realised when looking back at his 2017 Stanford interview.

That’s around when, he claims, that he decided to change the game in a self-professed quest to live a more “authentic” life and “make a difference”. By the next year, he had a new partner, the Italian pharma heiress Nathalie Dompé, and a rejigged business.

The big switch to SPAC

Mid-2018 was a period of huge churn for Social Capital, with some commentators writing its obituary, citing the cause of death as an “ego-fuelled collapse”.

The symptoms included Palihapitiya deciding that his company would no longer raise funds like a usual venture capital firm, and two co-founders and several senior executives quitting as a response.

In a Medium post in September that year, Palihapitiya announced wryly that “reports of our death have been greatly exaggerated” but that going forward Social Capital would no longer be accepting outside capital; instead, it would “become a technology holding company that will invest a multi-billion dollar balance sheet of internal capital only”.

In effect, Social Capital switched from the traditional venture capital model — which looks to sell its stake in the investee startup as fast as possible to profit quickly — to a more permanent model of investing, where investors take a more long-term approach to building and nurturing the company into a sustainable business. The new approach would be closer to what Warren Buffet’s Berkshire Hathaway does.

Since 2018, Social Capital has launched two SPAC platforms, Social Capital Hedosophia and Social Capital Suvretta, to give companies another way to go public. Social Capital now invests in areas like climate science, the life sciences, crypto/ decentralised finance, and deep tech.

Boom and bust?

So far, Palihapitiya has been part of 18 SPAC deals.

Through his tweets, his CNBC appearances, by backing the retail investors on Reddit’s WallStreetBets group against established Wall Street investors, Palihapitiya built legions of support for himself and his causes, like the SPACs.

There was a time when stock the price of Virgin Galactic, Palihapitiya’s first completed SPAC deal, was up a whopping 172.9 per cent.

Soon afterwards, as investors realized the markets were going cold on SPACs and that the Palihapitiya charm on the SPAC stocks was fading, some started writing his business obituary yet again.

Others questioned his integrity. As one Bloomberg profile noted, tongue in cheek, Palihapitiya was doing “just fine”, buying himself a US $75 million Bombardier Global 7500 jet, even if the SPAC bubble was bursting.

The profile claimed that with his outspoken and blunt style, he seemed “like the kind of guy who’d take pleasure in calling BS on current stock market hype — if he wasn’t the one behind it.” In other words, that he operates rather like a highly sophisticated confidence trickster.

This August, an Insider breakdown of Palihapitiya’s SPAC track record came with a warning of “double-digit losses” for investors.

As for Palihapitiya, he doesn’t seem to be too broken up about the write-offs, perhaps on account of having already survived a round back in 2018.

He still appears to be going about his life, tweeting, announcing deals, and doing podcasts with three of his “besties”— David Friedberg, an ex-Googler who later started up and sold his firm for a billion dollars; Jason Calacanis, a reporter turned entrepreneur and investor, and David Sacks, who sold his company to Microsoft for $1.2 billion.

The four talk about everything from startup fundings, to world politics and climate. One episode even talked about Sri Lanka when the country was facing its political and economic crisis. Palihapitiya shared how he and Google tried to introduce a free internet service via ‘Google Loon’ in Sri Lanka but they eventually backed out after (apparently unfounded) allegations that they were trying to steal spectrum.

Meanwhile, late this month, Palihapitiya’s SPAC jumped nearly 200 per cent in after-hours trading after his deal with the digital medicine company Akili.

As for the credibility of SPACs in general, potential investors would be well-advised to remember that everything is subject to market risk, so due diligence can never be delegated. Not even to your brown brother from another mother.

THE PRINT