| As economists point out, a default would result in Sri Lanka facing higher interest rates and an even lower credit rating among creditors |

The Governor of the Central Bank said last week, Sri Lanka has earmarked $ 500 million to repay a maturing sovereign bond on 18 January. However, several business leaders said Sri Lanka should take a rain check. Dr. Shanta Devarajan a former acting chief economist of the World Bank said honouring the maturing debt was reckless for two reasons.

The Governor of the Central Bank said last week, Sri Lanka has earmarked $ 500 million to repay a maturing sovereign bond on 18 January. However, several business leaders said Sri Lanka should take a rain check. Dr. Shanta Devarajan a former acting chief economist of the World Bank said honouring the maturing debt was reckless for two reasons.

Firstly, Dr. Devarajan noted, “Sri Lanka is facing an acute shortage of foreign exchange – people queue in long lines to buy cooking gas; there is no powdered milk; food prices are rising rapidly; power cuts are becoming frequent. This $ 500 million could enable people, especially poor people, to buy and cook food for themselves and their children. Instead, the Government is choosing to reimburse bondholders, who are hardly poor. Secondly, Dr. Devaraja noted, “Sri Lanka’s debt is unsustainable. Repaying maturing bonds in full today does not change that. It increases the chances that the country experiences an uncoordinated default in the near future. In this scenario, the country stops paying its bills because it cannot. The consequences of such a badly managed default can be devastating.”

Ceylon Chamber of Commerce Chairman Vish Govindasamy said in a release, “Sri Lanka’s debt and forex situation is affecting day-to-day livelihoods. Many restrictions have been imposed to preserve forex in order to service debt. However, it is best for GOSL to find a mechanism to restructure the debt and allow the use of inflows of forex to ease the general public’s difficulties in obtaining essentials. Further he noted, “Since the majority of GOSL comes from tourism, we cannot afford to send the world messages of food shortage in the country; it will only be counterproductive. COVID is a pandemic and GOSL does not have to blame itself for the issues created by it, we need to seek help from international organisations to resolve and restructure our debt.”

|

| Finance Minister Basil Rajapaksa |

|

| Central Bank Governor Nivard Cabraal |

Impact of a default

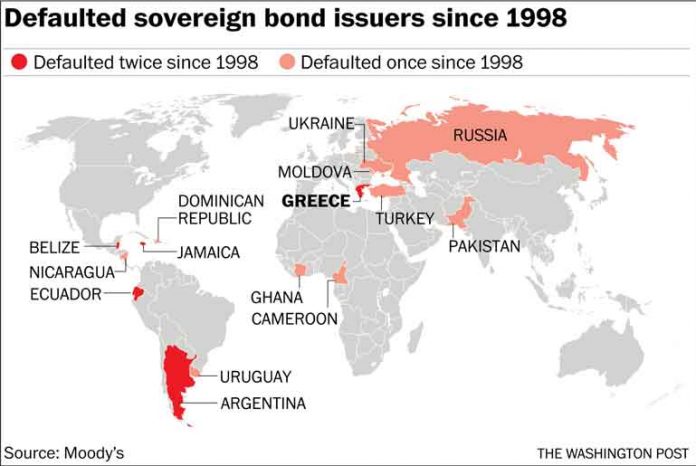

A sovereign default according to textbooks is the failure of a government to meet a principal or interest payment on

the due date. Argentina, Greece, Ecuador, Russia, Pakistan and Ukraine have defaulted in the past. So, if Sri Lanka decides to default, it is tantamount to a refusal to comply with a previous payment agreement. This will lead to a loss of confidence in Lankan businesses and the economy. Research suggests the European sovereign debt crisis was a period when several European economies experienced the collapse of financial institutions, high government debt, and rapidly rising bond yields. Therefore, a non-negotiated default will undermine the stability of the Lankan financial systems and will hugely impact economic growth as well as create economic turmoil.

Therefore, as economists point out, a default would result in Sri Lanka facing higher interest rates and an even lower credit rating among creditors. The world will also construe the default as a sovereign insolvency. Therefore, the bottom line must be – no default. The effects can linger for decades to come. Raising more ISBs would be nigh impossible, pushing SL into the clutches of the multilateral agencies and into bilateral deals, which always come with politically unpalatable conditions and high overall cost.

Options

Sri Lanka unfortunately as a result of years of overspending and grandiose projects using new debt to settle deficits by borrowing from domestic and international investors, has mortgaged the livelihoods of several generations yet unborn. It is time we hold those responsible accountable. Debt restructuring was certainly an option some months back, essentially that is renegotiating the outstanding debt to increase the payment terms, swap the outstanding debt in exchange for other terms. Unfortunately, this is not possible one week before a maturity. Sri Lanka since the pandemic has relied on short-term borrowings. This has created a mismatch between the short-term sovereign bond and the long-term value of assets/projects financed through forex debts.

Those who suggest a default or deferring must know the economic impact of a default on domestic banks’ balance sheets and their going concern. Especially, a massive-depreciation of the currency can have significant consequences for many private firms and banks. This could result in the country virtually shunned from accessing international capital markets. However, according to economists Rui Esteves, Seán Kenny, Jason Lennard an article titled ‘The aftermath of sovereign debt’ says, “On average, debt crises leave temporary, not permanent, economic scars. In this sense, default is not destiny. However, within this result hides a large heterogeneity. This has an obvious bearing on policy. Recognising that not all defaults are created alike can potentially improve the targeting of policy intervention; ex-post to smooth the impact of, or prevent, spillovers from a debt crisis.”

Conclusion

Therefore, of the 500 m, the foreign bondholders should be settled on maturity. We will then technically not be in default and that component is very low – probably 10%-20% or less. The rest are held by local banks, who profited from the sell-off and high yields, benefitting their financials and PATs and now need to take the pain of a GOSL mandated deferral on repayments. A rollover can be interpreted as default by international markets, but not a phased deferral of settlements. This would then address the valid concerns raised by several business leaders. The Government must therefore act professionally and do what is best for the 22 million people this time. In fact, as pointed out by several top economists, Sri Lanka should have sought the support of the IMF in Q1 of 2020. Whoever advised the Government not to do so must held accountable.

DAILY FT