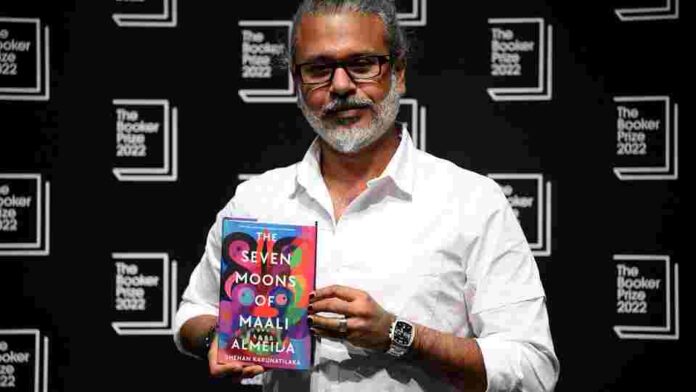

The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida has won the Booker Prize 2022, and a few weeks earlier we spoke to Shehan Karunatilaka about the legacy of his country’s civil war, his publisher’s tough love… and exploring the afterlife

How does it feel to be longlisted for the Booker Prize 2022, and what would winning mean to you?

To make any longlist requires luck. To get longlisted before the UK launch of your book is an extra bit of fortune. To have a novel about Sri Lanka’s chaotic past come out just when the world is watching Sri Lanka’s chaotic present also requires an alignment of dark forces. Unlike my protagonist Maali Almeida, I don’t gamble. So I don’t expect to roll two more sixes, though I will scream with joy if I do.

What was the starting point for The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida? Was it a slowburn idea or a moment of clarity? What made you want to write this particular book now?

I began thinking about it in 2009, after the end of our civil war, when there was a raging debate over how many civilians died and whose fault it was. A ghost story where the dead could offer their perspective seemed a bizarre enough idea to pursue, but I wasn’t brave enough to write about the present, so I went back 20 years, to the dark days of 1989.

What does your writing process look like? Do you type or write in longhand? Are there multiple drafts, long pauses, sudden bursts of activity? How long did The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida take to write?

It took too long. I began writing in 2014 and went through multiple versions, but maybe it needed that amount of time to evolve. First, I researched 1989, studied supernatural folklore, collected ghost stories and filled A3 sheets with notes in pencil. Then I typed an outline. And did beats for every chapter. Of course, the outline kept changing, as did the beats, and the ideas. But as soon as Maali’s voice emerged, the story began to find its rhythm, and five years later was ready to be read.

You’re one of several writers on the longlist published in the UK by small independent publishers – what does that mean to you, and how does it affect you as a writer?

It’s wonderful to be with a publisher who cares about the work and is able to give the story the tough love it needs. I’m not sure a larger publisher would’ve been as patient and generous as Natania Jansz and Mark Ellingham at Sort of Books were with Seven Moons, and its author.

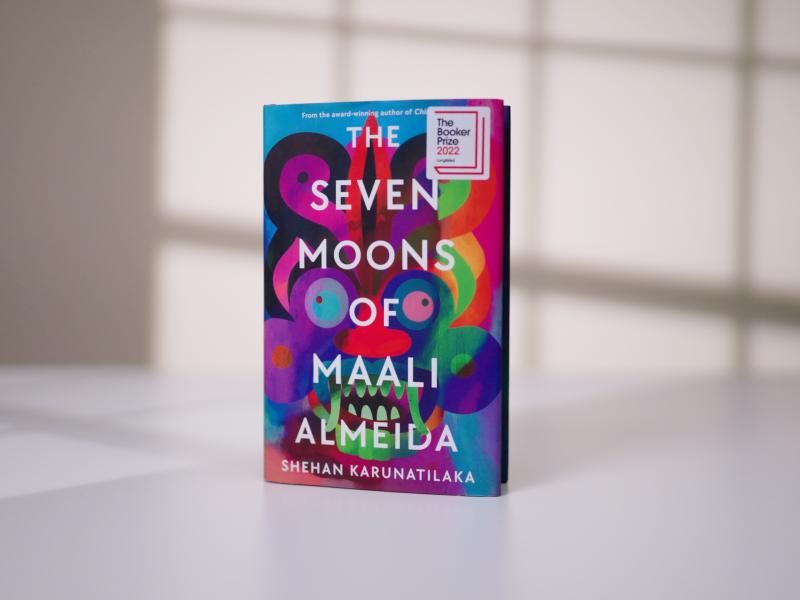

We worked steadily through the pandemic to make sure the strange plots and off-kilter characters were easy to digest. Then Peter Dyer created that brilliant cover. It was a true team effort and we’re all delighted to share this success.

One reviewer described The Seven Moons… as ‘part ghost story, part whodunnit, part political satire’. Is that a fair description, or are there other significant ‘parts’ that potential readers should know about?

Three balls is plenty to be juggling. So yes we had the mystery, the afterlife and the politics to balance the narrative. But there’s also a love triangle at the heart of this, some tender relationships and a fair bit of ghostly philosophising. Though hopefully the reader is too caught up in the story to notice the many moving parts.

For those who might not be very familiar with Sri Lanka’s civil war, what made you decide to set the book in 1989? What’s the significance of that year and what are the parallels between Sri Lanka then and now?

1989 was the darkest year in my memory, where there was an ethnic war, a Marxist uprising, a foreign military presence and state counter-terror squads. It was a time of assassinations, disappearances, bombs and corpses. But by the end of the 1990s, most of the antagonists were dead, so I felt safer writing about these ghosts, rather than those closer to the present.

I’ve no doubt many novels will be penned about Sri Lanka’s protests, petrol queues and fleeing Presidents. But even though there have been scattered incidents of violence, today’s economic hardship cannot be compared to the terror of 1989 or the horror of the 1983 anti-Tamil pogroms.

We all pray it stays that way.

Although set against a backdrop of violence, the book – like your first novel, Chinaman – is very funny. The Booker judges described it as being ‘angrily comic’. Is that the tone you were aiming for and, if so, why?

Despite having a grim history and a troubled present, Sri Lanka is not a dour or depressing place. We specialise in gallows humour and make jokes in the face of our crises. Just look at the zany footage of the July 9 presidential pool party and the many memes surrounding the Aragalaya.

Laughter is clearly our coping mechanism. In Chinaman, I used the archetype of the drunk uncle, and for Seven Moons it was the closet queen. Both characters are known for a dark and cruel sense of what’s funny.

Do you ever imagine your own afterlife? If so, how does it compare to the one you’ve invented here?

In the course of researching this, I didn’t encounter any ghosts or have any convincing epiphanies on the hereafter. But I’m not sure if any of the great ghosthunters or famous spiritualists have either. Who’s to say my version of a disorganised bureaucratic afterlife with an absent God isn’t the correct one?

1989 was the darkest year in my memory, where there was an ethnic war, a Marxist uprising, a foreign military presence and state counter-terror squads.

An earlier version of The Seven Moons… was published in India in 2020 as Chats with the Dead, yet it seemed to take a while to find an international audience. Why do you think that was and how did it change in becoming The Seven Moons…?

They’re both the same book, though Moons is perhaps less esoteric to a western reader and more accessible to an audience who know nothing about Sri Lanka or its ghosts.

You’ve written a children’s book and, according to Wisden, the second-best book about cricket ever written – as well as rock songs and copy for advertisements. What are you working on next and how different from The Seven Moons… will it be?

I am working on a few new projects, but none of them will feature cricket or ghosts.

You’re the second Sri Lankan writer in two years to be nominated for the Booker. Have western audiences finally woken up to the quality of Sri Lankan writing or is it just in a very strong place right now? Which other Sri Lankan writers should people be reading?

There’s no shortage of compelling stories in Sri Lanka’s past or present. When I started writing Carl Muller, Romesh Gunasekera, Shyam Selvadurai and Michael Ondaatje were the gold standard. As well as Arthur C. Clarke, whom I very much claim as a Sri Lankan writer.

Today, we have literary stylists like Anuk Arudpragasm and Nayomi Munaweera, genre storytellers like Yudhanjaya Wijeratne and Amanda Jay, comic scribes like Ashok Ferrey and Andrew Fidel Fernando, and dozens of talented writers like poet Vivimarie Vanderpoorten and essayist Indi Samarajiva.

And this is just in English. Hopefully, a new generation of translators can bring contemporary Sinhalese and Tamil works to a wider audience.

Do you have a favourite Booker-winning or Booker-shortlisted novel?

Just one? Could easily do a top 10, but I’ll stop at 5.

Lincoln in the Bardo. Cloud Atlas. The Handmaid’s Tale. Girl, Woman, Other.

And, of course, Midnight’s Children.