Set during the Sri Lankan civil war and narrated by a dead man, The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida is part murder mystery, part political satire and part love story. Its author recalls the grim events that inspired it – and the editor who kept pushing him to do better

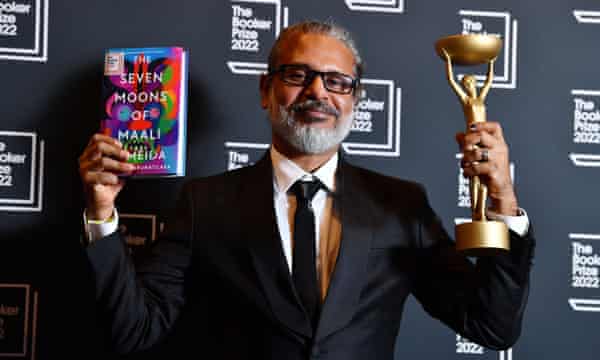

When Shehan Karunatilaka woke in his hotel this morning after winning the Booker prize – becoming the first Sri Lankan novelist to do so since Michael Ondaatje won for The English Patient in 1992 – he had more than 300 unread WhatsApp messages, but also tweets from Sri Lanka’s president, the leader of the opposition and other politicians congratulating him. These were met by a furious response from Sri Lankans, who “piled back on them saying: ‘Stay away from this guy. He’s writing about YOU,’” Karunatilaka paraphrases when we talk a little later that morning.

A spirited magical-realist epic, The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida is set in 1989 during the Sri Lankan civil war. Narrated in the second person, it follows Maali Almeida, “photographer, gambler, slut”, not to mention ghost, who has seven days to find out who killed him, and lead his two best friends to a stash of photographs that will show the world what is really happening in Sri Lanka. As Almeida explains in a handy crib sheet of his nation’s warring factions: “Don’t try and look for the good guys ’cos there ain’t none.”

It is 12 years since Karunatilaka’s first novel, Chinaman: The Legend of Pradeep Mathew, which used a quest to find a missing cricketer to explore a later period in Sri Lankan history, was published. (It won the Commonwealth book prize in 2012, as well as being voted one of the best cricket books of all time by Wisden.) Seven Moons – part murder mystery, part ghost story, part political satire and part gay love story – took him almost as long to write. “It is as old as my eldest daughter, who is now eight,” Karunatilaka, 47, says. While having two small children didn’t help (“Every time they come through the door a paragraph is removed from your head”), he can’t blame them entirely. “It was just such a complicated story.”

He was “incensed” when George Saunders’s Lincoln in the Bardo, “another talking ghost book”, won the Booker in 2017. “I was struggling with this thing, and it was a mess, and another talking ghost book won the Booker. It’s a masterpiece.” But he pressed on with his own ghost story. The only people who know the truth about the Sri Lankan civil war, he has said, are the dead. “So why not let them tell their own story?” And the whodunnit conventions proved the perfect framework for all the different factions, he says. Who killed Maali? There are five suspects who all wanted him dead. And the author worked hard on the love triangle that provides the novel’s heart. But Karunatilaka is not sure it’s fair to call the book a political satire. “I was describing things pretty accurately,” he says. “Maybe I do it with a bit of a smirk, but these were the events.”

Trying to give a résumé of the past 40 years of Sri Lankan history as we chat, he shows why the novel was such an ordeal to write. “If I was plotting a thriller I would say: ‘Way too many plots,’” he observes. “But this is actually what happened.”

Seven Moons was published in India titled Chats with the Dead in 2020, but it was proving too difficult for an international audience. So he sent it to his editor friend Natania Jansz, a fellow Sri Lankan who had set up the independent UK publisher Sort of Books with her husband, Mark Ellingham (they also founded the Rough Guide travel series). “People in publishing are awfully polite,” he says. She told him: “Terrific work, but I’m afraid that the middle and the beginning and the ending don’t quite work,” he says, laughing. It was just before lockdown when she took it on, so there were a lot of emails and Zoom calls to London. “She could have also said: ‘OK, it’s good enough’ and let it go. But thankfully, she kept pushing. So that was two years of work, but obviously it paid off.”

For an author who had to self-publish his first novel and who, despite its success, had great difficulty selling his second novel, to go on to take one of the English-speaking world’s most distinguished literary awards is quite a story. While winning the Booker is clearly a breakthrough – “It’s still sinking in” – he doesn’t see the rest of his experience as that unusual for a Sri Lankan author. “We don’t expect to be published outside Sri Lanka,” he says. “If we can get into India, Pakistan or Bangladesh, that’s an achievement, but it’s not guaranteed.” When he was growing up, writers such as Ondaatje and Romesh Gunesekera had global readerships, but they were writing from places such as Toronto and London. “For someone working in Colombo … well, you didn’t expect that. And still there’s only a handful of Sri Lankan writers who get published internationally. Hopefully, this will all change with Seven Moons.”

While he didn’t feel comfortable returning to the riots of 1983 and the start of the war – “I’m not part of the people who suffered” – he does recall the events of 1989. Growing up in middle-class Colombo in the late 80s, Karunatilaka says he was fairly “insulated” from the worst of the fighting, but he vividly remembers the curfews and schools closing, and his mother making him look the other way to avoid dead bodies or burning tires in the streets. His wife, whose family lived on the plantations, had a much more brutal experience of the war, he says.

Although this period has been well documented, he feels people still haven’t dealt with it emotionally. “Those who have memories don’t talk about it. We should write about it and try to make sense of it, because we don’t tend to do that in Sri Lanka – we tend to just move on.” As he explains, going back 30 years also felt “much safer”, as very few of the people are still around. “None of the factions exist,” he says. “No one is going to take offence because no one is around to take offence.” Hence all those chats with the dead.

Seven Moons’ afterlife is a sort of crowded visa office, which may have come from Karunatilaka spending too much time in various queues and offices, where he would use the time to make notes. “But the idea that the afterlife is confusing, and no one quite knows the rules, had a comic tinge to it, which is very much my sensibility.”

He tried writing in a serious tone, he says, but “often got bored with it”. The novel’s dark humour reflects not only his own outlook, but also that of the nation. “One thing is the smile,” he says. “We smile a lot.” But he has noticed that “the smile happens when we’re angry, when we’re confused. We don’t like confrontations. We prefer to save face, and always with humour.” Social media has enabled citizens to challenge leaders in a way they might never have dared before, he says. “Making jokes about the situation has kind of robbed the tyrant of their power. It is part of the Sri Lankan experience. And that’s why the country is not a miserable place, even though it’s got very good reasons to be miserable.”

Karunatilaka says his job as an advertising copywriter helped him as a novelist. You can’t get too hung up on axing your best ideas, and there’s no room for writer’s block: “You can’t tell clients: ‘I’m not inspired.’” Despite the Booker, he has no plans to give up the day job just yet. And he will stick to his routine of writing between 4am and 7am. “It is the only time. There’s no one to distract you, your social media is silent, your kids are asleep.”

He likes having several projects on the go. He’s also written and published a series of books for toddlers with his brother, an illustrator. “I realised spending seven years to write literary novels that may or may not get read is a tough gig. Then I had kids and discovered everyone has The Very Hungry Caterpillar, which sells 1m copies every year. I told my brother, ‘Let’s find our The Very Hungry Caterpillar.’” They produce about two books a year with titles such as Please Don’t Put That in Your Mouth and Where Shall I Poop? “And you’ve got your focus group right there with your kids. It’s a fun thing.”

In his teens and 20s, he wanted to be a rock star. “We all secretly want to be rock stars,” he says of the number of writer/musicians out there. He has five guitars and recently bought himself a drum kit. He taught himself to play the keyboard during lockdown. “You write for two hours, you take a break and you jam on the guitar. I just do it for myself. I don’t think there’s going to be an album or any band being formed.”

I notice the nails on one of his hands are painted black. “Yeah, this is my juvenile wannabe rock star thing,” he admits. “I always painted my nails black so it looks good when I’m playing guitar. It’s my fretting hand.” His wife does not approve of his “male polish” as he calls it. She said: “You’re going to the Booker, you’re gonna meet the Queen Consort, you can’t have nails like that.” So she took him to the salon for a manicure and pedicure before they left Sri Lanka. That was a mistake, he says now. Sitting in front of a professional manicurist, he couldn’t resist asking for “some black things. And yeah, my wife didn’t speak to me that afternoon.” He laughs again. “I was very proud that I held the Booker prize up with my black male polish.”

He is also proud that he managed to squeeze in short speeches in Sinhalese and Tamil at the Booker ceremony. His parents spoke Sinhalese, but the family spoke English at home. His children are trilingual and he is learning Tamil with them. “It was important to me that I was able to speak in those two languages.” He made a crack about the Sri Lankan cricket team losing the other night. And he added: “All Sri Lankans: let’s keep telling our stories. And let’s keep sharing our stories and listening to the stories of others.”

His dream for Seven Moons is that in 10 years’ time, readers in Sri Lanka will regard it as fantasy, “because the Sri Lanka that they live in does not resemble this”. He hopes people will say: “Did that really happen? Did you make this stuff up?” But, he continues: “Sadly, people are now drawing parallels between today and then.”

His immediate concern for the novel is to get as many as possible into bookshops back home. Getting hold of copies has been “a real problem”: several thousand have been “smuggled in”, he says. He was unable to read the other writers on the Booker longlist because the economic crisis in Sri Lanka is so bad that books are not considered a priority. He also made a gag in his speech about the current economic situation in the UK. “We’ve had three prime ministers in three months; I wonder if the UK is in for the same thing,” he jokes now.

He’s already started on his next novel. He didn’t want there to be the same long gap as between the first two. “There’s no cricket and there are no ghosts,” is all he will say.