US could be turning the corner on the pandemic, but not if you are one of the many people who has lost loved ones or is suffering post-coronavirus symptoms known as long Covid

Pamela Swan Addison keeps hearing the same phrases over and over. People are tired. They are tired of wearing masks, tired of getting vaccinations, tired of their lives being disrupted. Addison is tired too. But she’s tired of different things. She’s tired of listening to people complain about masks and vaccinations and disrupted lives when she knows her life will never be the same again.

She’s tired of the inevitable question people ask her whenever they discover her husband Martin died of Covid early in the pandemic aged 44: did he have an underlying health condition? He didn’t, as it happens, but why do they have to be so insensitive?

She’s tired of the conspiracy theories and fabrications. “One person commented my husband didn’t die of Covid, the hospital was paid to lie to me to inflate the numbers. How could someone say that to a widow who was grieving?”

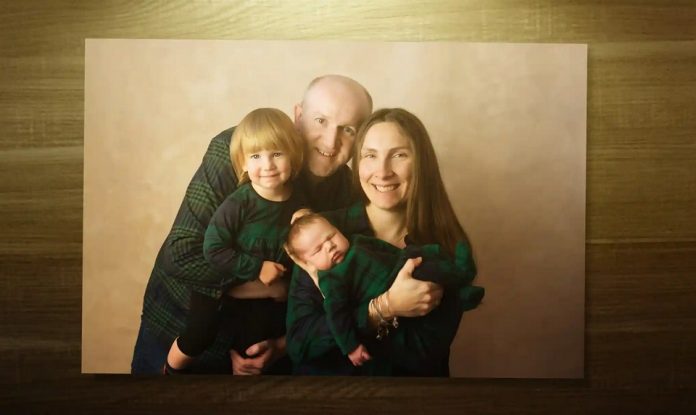

She’s tired of the thought that her husband, a frontline health worker who died in April 2020, has been all but forgotten. He gave his life serving his patients in a New Jersey hospital like a soldier who falls in battle, leaving her to care alone for their two-year-old son Graeme and three-year-old daughter Elsie, but where is the recognition?

All of this negativity frustrates and saddens her. She set up a group for young widows and widowers of Covid-19 so that others could share their experiences, and they all say the same things.

“We talk about how ignored we feel, how our kids are the forgotten grievers. People keep saying this disease is not so serious. But it is. It has killed almost a million people.”

Two years ago Sars-Cov-2 penetrated the United States, tentatively at first and then with a terrifying roar. On 11 March 2020 the World Health Organization declared Covid a pandemic, and two days later Donald Trump announced a national emergency, adding the memorable disclaimer: “I don’t take responsibility at all.”

Now two years into the global pandemic, hope is in the air that the US might finally be turning the corner. The Omicron surge is abating, mask mandates are being scrapped and vaccination requirements lifted even in Democratic states where public safety stances have been most stringent. Music festivals are being planned this summer with no Covid restrictions.

But the more the Covid cloud appears to be clearing, the more it becomes apparent that the consequences of the virus are likely to stick around. As Addison said, it’s hard to put behind you a disease that has killed almost 1 million people in America alone.

Ashton Verdery, a sociologist at Pennsylvania state university, created with colleagues a bereavement multiplier that estimates how many people in the US have lost a close relative to Covid. Given the paucity of historical demographic data for Hispanic and Asian Americans, they based their calculations on population statistics for white and Black Americans though they are confident their conclusions apply broadly to all US residents.

Verdery was taken aback by the findings. The number affected by Covid bereavement was much larger than he had expected.

Verdery and the team concluded that for every person who dies of Covid in the US there are almost nine people in their immediate kinship group left bereaved. For every grandparent who dies there are on average four grandchildren mourning them, every parent two children, every sibling two brothers or sisters left behind.

That amounts to a total pool of Covid bereaved people in the US of about 8.5 million, including almost 4 million Americans who have lost a grandparent and more than 2 million who are grieving the loss of a parent.

Verdery told the Guardian that he had been particularly struck by the large numbers of people who lost a grandparent. “Many children will remember for the rest of their lives that they lost a grandparent in the pandemic.”

The implications are especially acute when children lose a parent – a position that now applies to more than 200,000 under-18s.

“That’s going to have big consequences,” Verdery said. “Children who lose a parent have a greater likelihood of dropping out of school, not attending college, criminal justice involvement, lower earnings and higher mortality in later life.”

The US could conceivably be turning the corner on the pandemic, but not if you are one of the many people suffering post-coronavirus symptoms known as long Covid.

There is so much we don’t know about long Covid, not least how many of the almost 80 million people in the US who have been infected with the virus are suffering the most common symptoms of prolonged disease – tiredness, breathing problems, joint or muscle pain, and difficulties with concentrating.

Eric Topol, professor of molecular medicine at Scripps Research in San Diego, said that the number of US residents suffering enduring problems is likely to be more than 10 million. Some of his medical colleagues who contracted the virus in the early days of the pandemic are still very debilitated, he said.

“This is going to be one of the lingering profound results. We are in the dark, we have no idea where this will end. We have no treatment that is effective, and there’s been not nearly enough given the millions of people adversely affected.”

For Topol, the story of the past two years has been that of the extremes of American capability. On the one hand, there is the story of the lightning-fast development of vaccines, which he calls “historic, momentous, the greatest biomedical triumph yet”.

A timeline he put together on his Twitter feed makes the point. The Sars-Cov-2 virus was genetically sequenced on 10 January 2020 – two months before Trump announced his “no-responsibility” national emergency.

Five days later the first mRNA vaccine was designed by the US National Institutes of Health in partnership with Moderna. Two months after that a trial began of a vaccine that has proven to be remarkably resilient at withstanding the mutational dexterity of this virulent disease.

Compared with this unparalleled example of scientific speed and ingenuity, Topol despairs at how the vaccines and boosters have been put to use. Or not put to use. “We botched the whole booster program in the US,” he said.

Americans have taken up booster shots at a dramatically lower level than other wealthier countries despite the relative ease with which they can be obtained. The latest estimate from the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) is that booster coverage is as low as 42%.

Expressed as a league table of countries, the US now ranks 67th for the proportion of its population that is fully vaccinated and 54th for boosters. “We should see those rankings and have a sense of blatant failure,” Topol said. “We had reasons to be the leader in vaccine use and yet we slumped into being a world laggard.”

The consequences of that failure continue to be felt in the US despite the leavening mood. Thousands of Americans are still dying each week, deaths which Topol believes are almost entirely preventable given the efficacy of boosters at mitigating the deadliness of the virus.

He sees the continuing costs of failure too in the burnout within his profession. “Colleagues are going for early retirement because they can’t take it any more, people are changing careers, we’re losing nurses. It’s palpable, the disenchantment. It’s not just burnout – it’s burnout squared.”

As Topol suggested, the problem is especially acute among nurses. The American Nurses Association has said it expects more than half a million experienced registered nurses to retire this year, adding to a shortage projected to exceed 1 million.

That leaves a healthcare system whose flaws have been amply displayed during the pandemic even more vulnerable should the virus mutate again into a new aggressive variant.

Danielle Allen, a Harvard professor and national policy leader on the Covid response, told the Guardian that the pandemic has exposed other fundamental fault-lines that have been festering in American society for the past 50 years. In her new book, Democracy in the Time of Coronavirus, she explores how the country’s flailing approach was in significant part rooted in its gaping wealth inequality.

She notes how at the start of the pandemic affluent Americans retreated to their vacation homes and Zoom bubbles, “much as ancient Romans and early modern British aristocrats used to retreat to villas and country estates in the face of plague”. Meanwhile, low-income workers in essential frontline jobs – large proportions of whom were African American and Hispanic – were forced to turn up for work in person, prompting Covid case and death rates to match.

That core disparity is reflected in the latest statistics. KFF reports that two years on the racial gulf in Covid experiences remains huge: when data is age-adjusted it shows that Hispanic, Black, and Native American and Alaska Native people are twice as likely to die from Covid as their white counterparts.

“The pandemic has been an X-ray on who holds power and the vast separation between those elites and everybody else,” Allen said.

Allen recalls vividly the initial shock of the pandemic as it swooped down on her community. “It felt like falling off a cliff with no bungee cord. There was a plunge into hunger, and we had one of the highest mortality rates in the country among older people even though we have one of the crown jewels of biotech right here in Massachusetts.”

That dichotomy spoke volumes to her. “We were one of the richest states in the richest country in the world – and people felt abandoned.”

Abandoned. That’s the word that Allen kept hearing from people describing their plight.

It leads her to draw a highly sobering conclusion in her book, that Covid taught the US a very dark truth about itself: “We don’t know, in conditions of emergency, that we will be OK together.”

Too many people, she argues, “were willing to abandon our elders” to the virus. Too many people were willing to abandon essential workers, young people, people of colour, rural Americans.

For Allen, hard questions hang in the air even as the pall of the pandemic dissipates. The hardest question of all is stated bluntly in her book.

“If, in conditions of emergency, we cannot count on support from one another, then how do the institutions we share together have any legitimacy?”

That’s another potential long-term legacy of the virus in the US – its impact on democratic institutions. Around the first anniversary of the pandemic Ashley Quarcoo, a non-resident scholar at the Carnegie Endowment, assessed the situation and came up with some reasons to be cheerful.

In an article for the Council on Foreign Relations she pointed to new methods of voting, particularly voting by mail, that contributed to a historic turnout in the 2020 presidential election. She also highlighted the eruption of new forms of civic activism that reached a peak in the summer of protests following the police murder of George Floyd.

“There may be a silver lining that could strengthen US democracy in the longer-term,” she wrote then.

What a difference a year can make. The Guardian went to Quarcoo and asked her whether, on the second anniversary of the pandemic, she was still optimistic.

“There’s been a backlash to the huge election turnout in 2020, with many states passing laws to restrict voting by mail,” she said. “There’s also been a decline in confidence about our election integrity provoked by Donald Trump’s claims of election fraud.”

She still sees residues of the collective activism that the pandemic helped unleash, but there’s less consensus around the search for solutions. “That sense of social solidarity and coming together in the summer of 2020 has given way to mistrust, both about how things work and between citizen and citizen.”

As America scrambles to get back to a “normal” that perhaps never existed, Quarcoo warns that the wounds of these brutal two years run deep. “The social fabric of the US is more brittle, fissures are more deeply exposed and starkly clarified.”

That poses a challenge, she said. She gave it a name: the long Covid of our democracy.