Existentialists Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus were once friends, but differences between them ultimately ended their friendship.

Life in Europe in the first half of the twentieth century was unstable; wars, economic crises, a pandemic—it was hard not to feel humanity was facing one “existential crisis” after another. One philosophical response to this historical context was the philosophy of existentialism. There were shared themes explored by “existentialists,” but also important differences between them all. Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus were no exception to this as the two began as friends examining similar inquiries, but they would eventually be led to different philosophical positions.

What Is Existentialism?

Existentialism is best understood not as a philosophical movement or tradition, per se, but rather as a group of thinkers approaching shared inquiries, particularly about human existence. While related inquiries date at least as far back as the Hellenistic philosophy of Stoicism, existentialism, as an exploration of a group of shared themes, is generally dated to begin in the nineteenth century with Søren Kierkegaard and Friedrich Nietzsche. All of these thinkers are united around exploring who we are and how we should live in response to the turbulent and seemingly foreboding forces of change sweeping Europe, which was especially during the time of Sartre and Camus in the first half of the twentieth century.

Biography of Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Sartre was born in Paris and lived from 1905 to 1980. He described his childhood as “suffocating,” feeling quite alone with books upon spending a lot of time at home, being raised by his mother and grandparents upon the death of his father. But he would go on to pursue the study of philosophy, receiving his degree from the prestigious École Normale Supériore in Paris. He also studied in Germany, where he discovered the phenomenology of Husserl and Heidegger, which had a big impact on his subsequent philosophy.

During World War II, Sartre was captured by the Germans, and he relates that this was another time he had a deep exposure to Heidegger. Upon his return to Paris as a citizen, having pleaded poor health, he eventually joined the resistance movement—this is when he first met Albert Camus, as they initially shared political ideals, but they would eventually experience a great rupture that would lead to the end of their friendship.

Biography of Albert Camus

Albert Camus was born in Algeria and died in France. He lived from 1913 to 1960. Both Sartre and Camus took on many roles in their writings; novelists, essayists, and playwrights, to mention some. Camus was raised in a poor working-class family, as opposed to the more middle-class lifestyle that Sarte experienced. They did share, however, being raised by their mothers and grandmothers upon the deaths of their fathers.

As an adult, Camus had a reputation as a womanizer; though he did not believe in marriage, he did marry twice, but he was known to commit adultery—in fact, it is believed that one of his wives attempted to commit suicide as a result of the consequent turmoil this caused her.

Growing up in French-occupied Algeria was a very different experience for Camus compared to Sartre, and this is part of what led to opposing political views—the main source of their disagreement. Sartre would come to advocate for communism as the ideal form of government and solution to the problems of his time, whereas Camus would be all the opposite as a staunch anti-communist.

Similarities Between Sartre and Camus

As with the others labeled “existentialists,” in his philosophy, Albert Camus was concerned with the lived situation of human beings. The direction he would take from here, however, was to focus on why it is absurd; thus, some consider his philosophy to be a “philosophy of the absurd” rather than “existentialism,” along with some other key reasons.

Atheism, Absurdity, and Nothingness

Both Sartre and Camus were atheists, which was an important foundation for their subsequent views. Both agreed that this gave human beings radical freedom. However, as we can see, Camus was not nearly as antagonistic toward religion as Sartre was. They both shared a relational view of human existence; that is, our existence is fundamentally lived through our relations with others. This can lead to a feeling of self-alienation that can be highly problematic. But as we will see, they differed on what the results of this were. Sartre argued that this is how human beings understand “nothingness,” whereas, for Camus, it is how humans introduce absurdity into the world.

For Sartre, “nothingness” is the gap introduced by our subjective consciousnesses to the objects in the world. This is what makes us radically free because it opens up a world of possibilities for seeing this distinction between the subjective and the objective. Our consciousness introduces nothingness into the world via the realization of possibilities because it is how we can see that there are things in the world and things that are not yet possible to be some time in the future. This is also manifested in how we relate to others; we see others as objects because we cannot directly experience their subjectivity, but we assume that they, too, have this subjectivity that introduces nothingness, possibility, and thus radical freedom into their lived situation.

For Camus, rather than nothingness, he argues that humans bring absurdity into the world when open to these possibilities; when human beings confront the world without any God to provide a deterministic reasoning and path, all that we are left with is a reality of the absurd. Life has no origins as a gift from divinity and, thus, is empty. It seems meaningless as there is no real point to anything we do, so to go on living is essentially “absurd.” We relate to the world and others via this absurdity.

Liberation Through Pessimism

While these views may both initially sound pessimistic, they are ultimately both meant to be liberating through their shared emphasis on radical freedom; there is no fixed essence to what it means to be human, and we are ultimately each free to create whatever kind of meaning and thus life we want. “Existence precedes essence,” Sartre famously declared. And for Camus, despite the absurdity of our human existence, there is also something very fulfilling about living with that reality—as in his famous example of Sisyphus, as the myth went, destined through punishment to eternally roll a boulder up a hill, only for it to fall back down for him to start all over, yet he still finds something meaningful in the way that he accepts his life as it is lived.

Differences Between Sartre and Camus

While Sartre permitted the label “existentialist,” Camus did not; as noted, his was more categorized as a “philosophy of the absurd.” Thus, there was an important rift between their philosophies, but it was especially in their political views that they diverged. While such a tense break naturally had many moments that led up to it, some particularly key events created this rupture.

One of these was Camus’s publication of The Rebel where he explored his view that we should focus on the present and emphasize non-violence and open dialogue, rather than some utopian future as advocated for by Sartre. As a communist, Sartre sought to combine existentialism and Marxism, which he somewhat contradictorily saw as not deterministic but rather what best expressed the communal lived situation of humans at the time.

Sartre understood humans to be radically free, which conflicts with the Marxist teleological vision of a determined future. He shared the Marxist view that individuals were being stifled and suffocated; society limited what their natural, complete freedom was. As a group, then, capitalism results in “us” and “them” as oppressed “objects” and oppressing “subjects” respectively. However, as we are truly free, we can also come together as a group to revolt against this and liberate collectively—“nobody is free unless all are free,” Sartre declared.

Importance of Sartre and Camus in the History of Philosophy

Despite these key differences between Sartre and Camus, among others, and despite the general critiques that can be raised against them both, they made important contributions to the long conversation that is the history of philosophy.

When Sartre died in 1980, there were said to be over 50,000 people who attended his funeral procession. Regardless of one’s level of familiarity with philosophy, many have heard the name “Jean-Paul Sartre.” In 1964 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, but he refused it; consistent with his non-traditional views, as a writer he said he did not want to “be an institution.”

Albert Camus did, conversely, accept the Nobel Prize for Literature prior in 1957—he was the youngest French writer to ever be bestowed that honor. Camus died in 1960 in a car accident, which was also eerily related to his view on the seemingly meaningless nature of the human lived situation and experience. Our freedom is something very paradoxical for Camus; it seems to be an illusion, but seeing this also is somewhat liberating, bringing freedom back in the way we respond to this. We must live life in the moment as fully as we can, for we never know when death will come—just as lived by Camus.

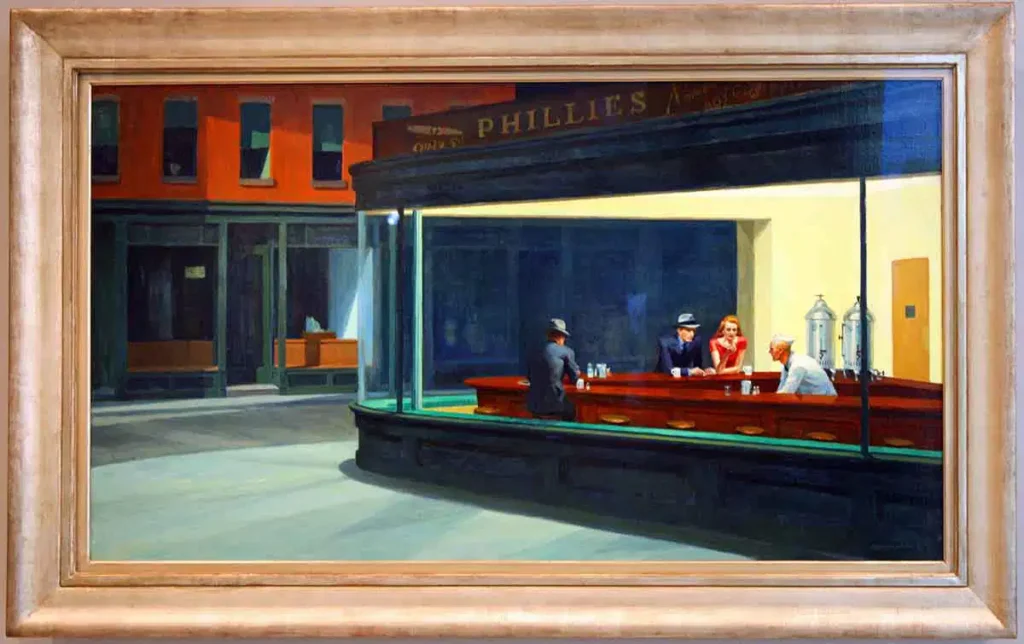

It is generally critiqued that existentialism is too unanalytic and too focused on emotions and the darker side of the human experience. However, the existentialists were reacting against the modern condition that they saw as relying too heavily on science, arguing instead that science cannot fully understand the human experience. Science, they argued, dehumanized our lived situation by turning us into objects, which the existentialists wanted to overturn. What cannot be denied is the profound influence existentialist thought had on more than just subsequent philosophies but also psychology, literature, and art.

Marnie Binder

(PhD Humankind and Thought in History)

Source: The Collector