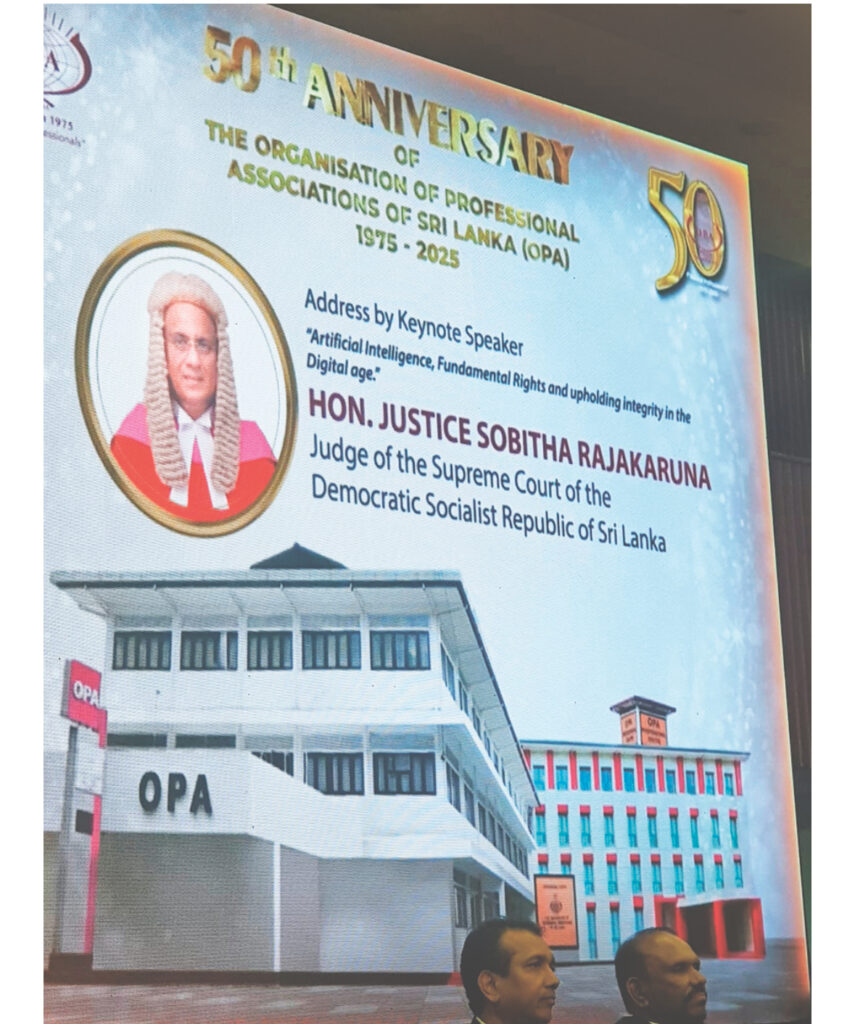

Dr. Nath Amarakoon Memorial Oration by His Lordship Justice Sobhitha Rajakaruna, Judge of the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka at the 50* Anniversary Celebrations of OPA delivered at BMICH on 29 May 2025

I am deeply honoured to have been invited to deliver the Dr. Nath Amarakoon Memorial Oration before this August assembly, where the Organisation of Professional Associations of Sri Lanka (OPA) celebrates its 50th Anniversary.

The OPA holds a special place in my heart for many reasons, particularly because I had the unique opportunity to engage with it during my period of apprenticeship, 33 years ago, even before becoming an Attorney- at- Law.

I have had the pleasure of working there in several capacities under several Presidents at the OPA, including those elected from BASL, such as the legal luminary Mr. Parakrama Karunarathna, who was a higher-ranking officer and my supervising officer at the Attorney General’s Department. Likewise, I must acknowledge the Attorneys- at- Law, the late Mr. Gamini Jayasinghe, Mr. Sena Lianasuriya and Mr. Serasinghe who aligned me with the activities and mission of the OPA.

Dr. Amarakoon Mudiyanselage Nath Amarakoon, the founder President of OPA, was a former Permanent Secretary to the Ministry of Housing, former Chairman of the State Engineering Corporation, General Secretary of the Eksath Sinhala Maha Sabhawa, Head of the Sanathana Foundation, Nawinna, and a committed Philanthropist. I have found, among many, that his commitment to the construction and commissioning of the Steel Factory at Oruwela and the Tyre Project at Kelaniya was tremendous. He was the beloved husband of the distinguished Dental Surgeon, Dr. Indrani Wijesinghe Amarakoon.

Dr. Nath Amarakoon was instrumental in founding and shaping the early growth of OPA in Sri Lanka, making a significant contribution that laid its groundwork. In 1972, together with other prominent professionals like Dr. H.W. Jayawardena, Queens’s Counsel and Dr. S.A. Cabraal, he engaged with Mr. John Chadwick, the Commonwealth Foundation’s first Director, to discuss forming a professional alliance to complement the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM). This effort sought to bring together Sri Lankan professionals from various fields to amplify their collective influence on National and Commonwealth goals.

On 29 April 1975, OPA was officially founded during a meeting at the ASTW headquarters, where its Constitution was adopted, and the first Office-Bearers and Executive Committee were elected. Dr. Amarakoon and other key members identified the need for a shared facility, as many member associations lacked permanent offices.

I have gathered through extensive research that Dr. Amarakoon’s efforts have become fruitful with OPA obtaining a substantial GBP 45,000 grant from the Commonwealth Foundation to build the present Professional Centre. An additional GBP 10,000 has reportedly been provided to complete the original structure. The Professional Centre, which was inaugurated in September 1982 by then President J.R. Jayewardene, now hosts numerous member Associations and serves as a focal point for professional activities, including Seminars, Workshops, and Research addressing National concerns.

Dr. Amarakoon passed away on 22 November 2017, at the age of 81 and his vision and organisational efforts fostered inter-sectoral collaboration, aligning with OPA’s mission to address National challenges through professional expertise.

With that note, I must now advert to my topic. I have selected to speak on — Artificial Intelligence, Human Rights and Upholding Integrity in the Digital Age. It would be relevant to first consider what Artificial Intelligence (AI) refers to. “AI is the simulation of human intelligence processes by machines, especially computer systems.” Alternatively, it could be defined as “the development of computer systems that can perform tasks requiring human-like intelligence.”

As judges, we are entrusted with safeguarding the Constitution and the fundamental rights it enshrines. In this rapidly evolving digital era, AI presents both unprecedented opportunities and profound challenges to our mandate. I have witnessed the judiciary’s evolving role in balancing technological advancements with the hallowed principles of justice and human dignity. I invite you to reflect with me on this duality: how AI can both fortify and threaten the structure of human rights, amidst the eroding element called integrity. Our legal heritage, rooted in Constitutionalism and the Rule of Law, demands a proactive response to this duality.

AI has emerged as a transformative force, reshaping industries, governance, and daily life with incredible speed and scale. Its capability to analyse extensive data, forecast results, and streamline decision-making offers significant potential to advance fundamental rights, while concurrently presenting serious dangers that jeopardise those same Rights. Bridging privacy, equality, freedom of speech, and access to justice, AI’s twofold character—as both an enabler of progress and a possible source of suppression- demands a delicate examination.

AI isn’t a physical item you stumble upon in a box, basket, or container, nor is it a consumable like food or a drink. Instead, AI resides within electronic devices, such as laptops, phones, or tablets, existing outside our bodies as a digital construct. Yet, through these devices, AI can metaphorically be ‘absorbed’ into our minds and lives, as we interact with its outputs, learn from its insights, or adapt to its influence at our choice. Far from being a tangible substance, AI is an external technological entity that we engage with, shaping our thoughts and actions through the tools we choose to wield. That’s how the component of integrity also comes into play.

On the other hand, your friend, neighbour or political opponent may wield AI in a way that infringes upon your rights by using AI-generated deepfakes to defame you, breaching dignity. In such an event, the affected individual would need to seek a remedy through a Court of Law, either to obtain compensation or to have penalties imposed on the perpetrator.

In my opinion, AI poses a threat not merely by its simple existence, but by how we apply it to our Rights and thoughts. Its capacity to configure privacy, equality, and justice — whether through surveillance, biased algorithms, or unclear evidence — transforms its relevance into a pathway for harm if not properly regulated. However, through strict supervision and principled or ethical development, we can steer AI’s impact towards empowerment, guaranteeing its strengths rather than its weaknesses as the foundation of Fundamental Rights. The decision rests with us: ‘shape AI into a protector of fairness or allow it to evolve into a danger we regret’.

AI may offer the Supreme Court a powerful tool to strengthen Fundamental Rights applications by refining evidence relevancy under the Evidence Ordinance, enabling faster, data-driven justice. Yet, this strength harbours danger: if AI’s analysis is flawed, due to biased training data, violation of patent or privacy laws or vague algorithms, it risks presenting distorted facts, skewing judicial outcomes. Judicial training in AI literacy, coupled with laws mandating accountability, can safeguard the rights of citizens. International norms, such as the UN Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary, reinforce that technology must serve justice, not subvert it. By reining in AI’s relevance with accountability, we can harness its potential while averting its peril.

AI’s danger, tied to its relevance, is not inevitable, but I believe that it can be tamed through good conscience and good governance. The challenge lies not in AI itself, but in our choice or discretion to wield it justly, safeguarding the dignity and rights of all living in a world where desirous and daily requirements are rapidly increasing on a ‘per second’ basis.

I need to highlight another interesting aspect here today. In crafting my speech and for the purpose of making it with practical experience, I turned to an AI app and fed it with the topic for today’s address. Certainly, it was only to find whether its output was attractively akin to my own thoughts — a revelation that sparked a dilemma. Had I delivered my original speech without looking at AI, some professionals familiar with similar AI-generated content might accuse me of plagiarism; yet, relying wholly on AI’s text would invite the same charge.

One may query why AI-assisted learning or linguistic borrowing should be deemed wrong. But, currently, the learning is always leant mostly on external sources such as books, Google, apps, or devices, and lectures.

Where do you get a law which prevents you from learning lawful subject content from reading or watching prima facie lawful substance through a legal app or an electronic device? Are we confined to outdated textbook methods, or can’t we embrace AI as a legitimate tool to sharpen our intellect?

This question challenges us to reconsider the boundaries of creativity, influence, patent and privacy rights and ethics in an AI-driven world. When AI engages with Fundamental Rights or judicial processes, its impact on these vital domains can heighten its potential for harm, transforming a tool of advancement into a threat that undermines privacy, equality, due process, and justice. AI does not inherently pose a threat through its influence on our rights and fact-finding processes unless we choose to exploit it for personal gain, thereby breaching the principles of good conscience or sound governance.

So, is AI a new era of protection or peril? The answer lies in our hands, as jurists, lawmakers, future leaders and other professionals like yourselves. We must craft legal frameworks that embed accountability into AI systems, mandating transparency and human oversight, much like the constitutional checks we uphold.

I have shared many of these thoughts when I was delivering a speech at a Law School in Pune, India during the month of March this year. There also, I spoke about a ‘vaccine’ and an ‘antibiotic’. The members of the legal fraternity together with policymakers – your task is to innovate legal ‘vaccines’ to shield the rights of individuals who integrate AI’s productivity into their personal experiences, while scientists and computer experts must develop advanced software- ‘antibiotics’- to evaluate and verify authenticity, protect patent rights, and uphold human dignity within AI’s domain. Together, with these efforts, we can steer AI towards empowerment, balancing its promise with the preservation of justice and humanity.

At the same time, I must stress that integrity and good conscience are the cornerstones of ethical living, serving as an internal compass that guides our actions, decisions, and interactions, even in the rapidly evolving digital era dominated by artificial intelligence (AI). Integrity embodies honesty, moral uprightness, and adherence to principles, while good conscience reflects an inner awareness of right and wrong, acting as a vigilant monitor of our choices. Together, they empower individuals to maintain their moral sovereignty, ensuring that no external force, be it AI or any third party, can compromise their values without their explicit or implicit consent and knowledge.

In this digital age, AI systems, with their vast capabilities in data processing, surveillance, and decision-making, may attempt to influence the behaviour of individuals. However, no AI or external force can dominate your mind or compromise your integrity without your permission, whether given directly or indirectly. Your integrity remains within your control, rooted in your ability to exercise free will and judgment.

For instance, while AI-driven platforms may nudge you towards certain choices, it is your conscious decision to accept or reject those influences that define your moral stance.

Good conscience operates like an internal CCTV camera, constantly observing and recording your thoughts and actions. It alerts you when you stray from ethical boundaries, ensuring that no act, whether in private or public, escapes its scrutiny. You cannot act without the knowledge of your conscience; it is an ever-present witness, urging you to align with what is just and true.

However much you meticulously plan to engage in wrongdoing under tight security, using AI or any other advanced methods, you cannot execute anything without the awareness and knowledge of your own conscience. The cleanliness of your conscience is eternally recorded, whether you like it or not, at the visa counter to heaven or hell. So don’t bring even a paper clip home from your workplace and don’t abuse your right to operate your official Photocopy machine to copy your child’s school notes. Such an act can be considered as ‘robbery’ or ‘corruption’ respectively although it appears in its miniature version. Public Servants and politicians, including Judges, should not expect rewards for their good service here other than in heaven.

This inner vigilance empowers you to uphold integrity, even amidst the pervasive presence of AI systems that may challenge ethical norms. Upholding integrity is, therefore, entirely within your hands and conscience. It requires active resistance to external pressures and a commitment to self-reflection.

Even in a robust AI-driven system, your conscience remains sovereign. By staying informed, questioning AI outputs, and prioritising ethical principles, you can safeguard your integrity. Ultimately, integrity and good conscience are your unassailable defences, ensuring that you remain the master of your moral destiny, no matter how advanced the digital landscape becomes.

So, I take the view that the AI’s peril is not inherent but crafted by human choices — its design, training, and application dictate its impact on rights and facts. As human beings, we have many desires. There is a kind of ‘monkey trap’ that is used in Asia. “The monkey smells the sweets, reaches in with his hand to grasp the food and is then unable to withdraw from it. The clenched fist won’t pass through the opening. When the hunters come, the monkey becomes frantic but cannot get away. There is no one keeping that monkey captive, except the force of its own attachment. All that it has to do is open the hand. But so strong is the force of greed in the mind that it is a rare monkey which can let go. It is the desires and clinging in our minds which keep us trapped.”

All we need to do is open our hands, let go of ourselves and our attachments, and be free. This greed suppresses the genuine conscience of any average human being. So, we should open our hands and let go of ourselves towards the genuine direction to overcome the bad and dangerous effects and shadows, if any, of AI.

One of the legal Interns who served in my Chambers- Ms. Theruni Hettithanthrige, when she was 12 years has authored a poem, titled A World Without Red? In her book “A Chocolate Box of Poetry”:

A World Without Red?

Red is the colour of the lips of a sophisticated lady Red is the colour of soil when it is shady

Red is the colour of a cheerleader’s skirt Red is the colour of a bullfighter’s shirt

Red is the colour of the traffic light

Red is the colour of a person who just threw a fight Red is the colour of a shy girl’s cheeks

Red is the colour of birds’ beaks Red is claimed to be the colour of danger

As well as love

Imagine a world without This amazingly bright colour.

I urge all of you not to paint AI with the vibrant shade of red a choice that could trap you in self-imposed limits, binding your life so tightly to its presence that living without it becomes unimaginable.

Finally, I need to thank the Executive Council of the OPA including the current President of the OPA who represents BASL and the Past President, Mrs. Ruchira Gunasekara, another representative of BASL for granting me this opportunity.