An army of nuns, farmers and middle-class professionals felt a duty to save their virtually bankrupt nation. But their fight is far from over.

By Mujib Mashal and Emily Schmall

COLOMBO, Sri Lanka — The president was cornered, his back to the sea.

Inside the dimly lit colonial mansion he had found lonely, Gotabaya Rajapaksa watched from a hastily arranged operations room as the months long protests demanding his ouster as Sri Lanka’s leader reached his very doorstep.

A former defense chief accused of widespread abuses during the South Asian nation’s three-decade civil war, Mr. Rajapaksa had taken an uncharacteristically hands-off approach toward the demonstrations. The message: He could withstand dissent.

But this largely middle-class movement — lawyers, teachers, nurses and taxi drivers incensed with an entrenched political elite that had essentially

bankrupted the country — was no routine protest. It kept swelling.

And now, in the late morning of July 9, thousands of protesters were massing in front of the seaside presidential residence, as hundreds of thousands of others flooded the capital, Colombo. Two wrought-iron gates and three barricades, all thickly guarded, stood between the demonstrators and the last standing member of the Rajapaksa political dynasty.

As demonstrators had marched toward the mansion, tear gas rained down, disorienting Dulini Sumanasekara, 17, who had camped for three months with

her parents, a preschool teacher and an insurance salesman, and other protesters along the scenic Galle Face in Colombo. After returning to the campsite to receive first aid, she and her family rejoined the protest.

“We were more determined than ever to make sure Gotabaya would be gone that very day,” she said.

By early afternoon, the mansion had been breached and Mr. Rajapaksa had slipped through a back gate, sailing away in Colombo’s waters and eventually fleeing the country. The protesters controlled the streets and seats of power — swimming in the president’s pool, lounging in his bed, frying snacks in his kitchen.

Interviews with four dozen government officials, party loyalists, opposition leaders, diplomats, activists and protesters sketch a picture of an unprecedented civic movement that overwhelmed a leader who had crushed a rebel army but found himself ill-equipped to address the country’s economic disaster and slow to grasp his support base’s rapid turn against him.

Three years after winning the election handsomely, and just two years after his family’s party had secured a whopping two-thirds majority in Parliament, Mr. Rajapaksa had become deeply resented. And the bill for his family’s years of entitlement, corruption and mismanagement, made worse by a global economic order plunged into chaos by Covid and war, had at last come due.

The Rise

Before his unlikely ascent to the country’s highest office in 2019, Gotabaya Rajapaksa had played second fiddle to an older brother who established the

family as a powerful dynasty.

Mahinda Rajapaksa rose to become president in 2005 on a promise to end the civil war. That conflict was rooted in systematic discrimination against minority Tamils by the majority Sinhalese Buddhists, the support base of the Rajapaksas.

Gotabaya eschewed politics and pursued a career in the military, retiring early as a lieutenant colonel in the late 1990s. He completed a degree in information technology in Colombo, and then followed his wife’s family to the United States, where he worked in I.T. at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles.

After becoming president, Mahinda put the former lieutenant colonel in charge of his generals and the war strategy.

As defense secretary, Gotabaya was ruthless and cunning, demanding nothing short of “unconditional surrender” by the Tamil insurgents, diplomatic cables released by WikiLeaks showed. The United Nations estimates that as many as 40,000 Tamil civilians were killed in the final months of the civil war alone.

Thousands of others disappeared, still unaccounted for. Gotabaya Rajapaksa has denied accusations of wrongdoing.

The Rajapaksas’ push to crush the insurgency came with a promise that economic prosperity would follow.

Shirani de Silva returned to her native Sri Lanka from Cyprus in 2006, a year into Mahinda Rajapaksa’s first term. By 2009, the insurgency was over and the island was once again open for tourism.

Ms. de Silva used savings to build a guesthouse and married a Sri Lankan who had also recently returned from working in Europe to open a restaurant and natural foods store.

By the time their son, Stefan, was born in 2011, both businesses were thriving. “I thought he would have a really good life,” Ms. de Silva said.

The family’s fortunes grew alongside the country’s. In the years after the war, economic growth was brisk, and the Rajapaksas turned to building — expansively. Leveraging the newfound peace, they borrowed huge sums, including from China, to build expressways, a stadium, a port and an airport.

In addition to being defense secretary, Gotabaya Rajapaksa was put in charge of urban development, bringing military precision and army muscle to efforts to beautify Colombo and improve town halls around the country.

Eventually, the Rajapaksas’ heavy hand and dynastic aims would fall out of favor. In 2015, Mahinda Rajapaksa was defeated in his bid for a third term. But as the governing coalition soon descended into chaos and bickering, the Rajapaksas slowly began their return to public life.

A faction of the Rajapaksas’ party rallied around Gotabaya as a technocrat who could mop up the political mess. He had a reputation as a doer and not a politician. He preferred short-sleeve shirts and Western pants to the brothers’ white robes and maroon shawls. The powerful Buddhist monks saw him as dedicated to the cause of the ethnic majority.

Mr. Rajapaksa was spending most of his time at home in Colombo. Travel abroad brought the risk of prosecution. During a visit to his old home in California, lawyers had tracked him down in a Trader Joe’s parking lot and handed him a notice of a tort claim by a person alleging torture.

It was ultimately a grievous security breach on Easter Sunday in 2019 that opened the door for the Rajapaksas to return to power. Suicide bombers targeted churches and hotels, killing more than 250 people. Intelligence warnings had been lost in the government’s infighting.

The country was gripped with fear; tourism came to a standstill. Entrepreneurs like Ms. de Silva worried that they could lose everything.

Desperate for security to be restored, Ms. de Silva and her husband were among the 6.9 million Sri Lankans who cast their votes for Gotabaya Rajapaksa in an overwhelming victory.

The Fall

His honeymoon would be brief.

Within months came the pandemic, which Mr. Rajapaksa answered with a familiar strategy: He deployed the army to carry out lockdowns and, eventually, vaccinations. But he was ill-prepared for the shock to an economy that had operated since independence on deficits, which had been deepened by Mahinda Rajapaksa’s reckless borrowing.

In one year, about $10 billion vanished from the economy as tourism dried up and remittances dwindled. In September 2020, some officials at Sri Lanka’s central bank suggested that the government approach the International Monetary Fund for help.

The administration “did not listen to our recommendations,” said Nandalal Weerasinghe, now the bank’s governor, who was deputy governor at the time. The president’s cabinet was divided, with party officials insisting that the country could avoid a bailout and the strings that would be attached, while Mr. Rajapaksa couldn’t decide.

Even as the economic crisis deepened, the president’s focus was often elsewhere. In April 2021, he suddenly declared a ban on chemical fertilizers. His hope, his advisers said, was to turn Sri Lanka into “the organic garden of the world.”

Farmers, lacking organic fertilizer, saw their yields plummet. And a rift in the family grew: Gotabaya resisted attempts by his brother Mahinda, who was now prime minister, to change his mind on the fertilizer ban.Mahinda’s return, after he had helped lead the party to a huge election victory, had weakened Gotabaya’s control by creating two centers of power. Eventually, the cabinet would be stocked with five Rajapaksas.

By the spring of 2022, long lines were forming for fuel, supermarkets were running low on imported foods, and the nation’s supply of cooking gas was almost exhausted as the government’s foreign reserves dwindled almost to zero.

The country was in free fall. And the one person who could do something about it was adrift. In meetings, the president was often distracted, scrolling through intelligence reports on his phone, according to officials who were in the room with him. To several of his close friends, he had become a prisoner of his own family.

The Backlash

Soon, small protests calling for the Rajapaksas to step down began popping up around the country. Eventually, Colombo’s Galle Face became a focal point.

Dulini Sumanasekara, the 17-year-old who began camping there with her family in April, toggled between volunteer service in the camp’s kitchen and online classes at home.

While she hoped to study medicine, Dulini, like all other students in Sri Lanka, had been kept out of the classroom — first by Covid and then by a government policy to go online to save fuel costs.

The crisis had also cost her mother, Dhammika Muthukumarana, a job at a private preschool. The family struggled to find and pay for essentials like milk powder and grains.

But it was less frustration, and more a sense of civic duty, that prompted Ms. Muthukumarana and her husband, Dhaminda Sumanasekara, to move with

their children to the Galle Face tent camp.

“We could feel it in our bones,” she said. “It was time to go stand up for our people and our country against the lies and corruption.”

As fuel became scarce, Mangla Srinath, a 31-year-old taxi driver, kept 20 liters of fuel in his bathroom, siphoned from his tank after he had managed to fill it.

His wife, Wasana, had breast cancer. He wanted to ensure that he had enough fuel for an emergency run to the hospital.

“Once a week, we would go to the protest in the evening,” Mr. Srinath said. “Sometimes, we would go on our way to the hospital.”

The protest site had grown into a civic space, a safe zone for the country’s religious, ethnic and sexual diversity. Some saw it as the long-delayed beginning of a conversation on reconciliation after the Rajapaksas’ postwar Sinhalese Buddhist triumphalism.

“People now openly talk about equality,” said Weerasingham Velusamy, a protester and a Tamil activist who works as a gender equality consultant.

“People talk about justice for the disappeared.” During a remembrance ceremony for the brutal pogroms against Tamils in 1983, Saku Richardson, a musician and a grandmother, leaned against her bicycle, holding a handwritten yellow sign that simply read “Sorry.”

“For 30 years, we didn’t do anything,” she said. “We didn’t protest.”

Ms. Richardson, who comes from a mixed Sinhalese and Tamil family, said a realization had set in among her friends that the country’s woes were a result of the impunity and entitlement of the military and political leaders after the brutal war.

“They feel that this is the curse of that,” she said. “That this is karma.”

The Collision

On the evening of July 8, the scene in the presidential mansion was frenetic, with lawmakers going in and out. The president, who didn’t sit down for a dinner of rice noodles and curry until close to midnight, was expecting, based on intelligence reports, a crowd of 10,000 protesters to gather the next morning.

Two months before, the movement to oust him had escalated sharply. Mahinda Rajapaksa resigned as prime minister, but on his way out, his supporters marched on the protest camp, fueling violent clashes that turned into a night of anarchy, with the houses of dozens of his party’s lawmakers set on fire in retaliation.

The president, Gotabaya, had received intelligence that his brother’s supporters were cooking up trouble, but he was unable stop it, according to officials who were with him that day. By early in the evening, he had nearly lost his voice from screaming on the phone, these officials said. To those in the room, his desperate calls down the chain of military and police command made clear he was losing control.

In the weeks that followed, Mr. Rajapaksa tried to project the clearing of his family members from the government as a fresh start, but the protesters were not appeased.

Now, on the morning of July 9, it was becoming clear that the number of protesters was much larger than expected.

Just before noon, as protesters pressed toward the mansion, they scrambled over the first barricade, in what many later called a spontaneous action. The barrier was quickly toppled by the crush of people who followed, pushing through volleys of tear gas. Once they had brought down two more barricades, a few protesters hopped the first of two gates to the mansion and unlatched it.

As the crowd reached the second gate, the last physical barrier between them and the president, the sound of gunshots rang out. Two people fell, wounded. Security forces rushed the protesters with batons.

Inside, it was clear the president was out of time. The generals told him it was time to go.

Video footage later emerged on social media of men rushing suitcases onto a navy vessel. The president was ushered through a back gate to the navy base behind the mansion. From there, he would set off in Colombo’s waters.

As he escaped, protesters hot-wired an army truck and rammed it through the final gate. Unable to hold the line, the security forces gave way. Hundreds of people flooded the compound, cheering and chanting as they filled the grand ballroom, climbed the spiral staircase, and occupied the president’s bedroom.

Among them was Ms. Muthukumarana, who felt a tinge of envy as she admired the expensive wardrobe of the president’s wife. That feeling quickly turned to anger, “realizing how much we had suffered to sustain their habits,” she said.

Mr. Srinath, the taxi driver, picked up his wife on his motorbike headed toward the mansion.

“The army guy told me, don’t worry, we will watch your bike,” he said. Husband and wife posed for a selfie on the stairway, Wasana still wearing her helmet.

Hours after the takeover, protesters put the word out that the mansion was now open to the public. Families waited in a line wrapping around the block to enter what had effectively become a free museum. Once inside, they studied the paintings and chandeliers, swam in the pool, sat around a long teak dining table and had picnics in the garden.

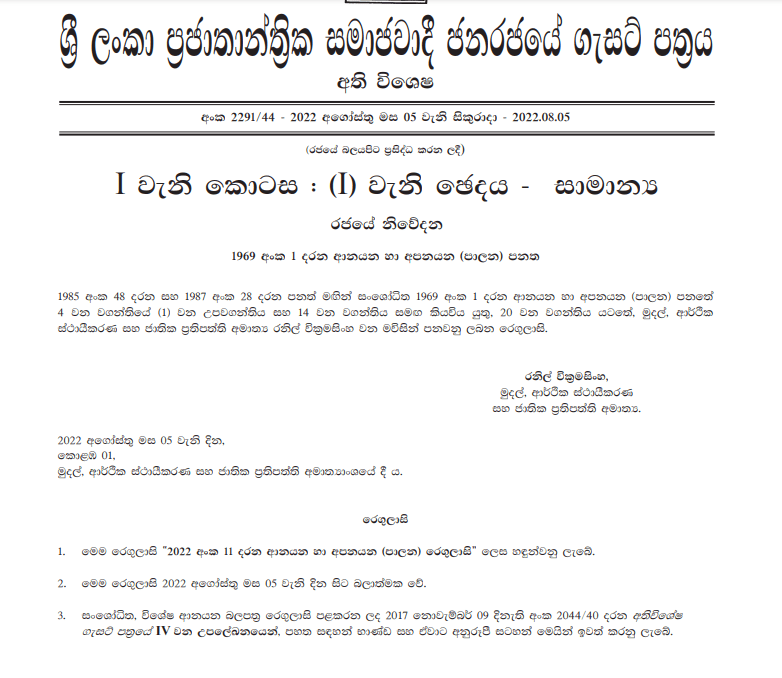

Order did not always prevail: By nightfall, a crowd had set Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe’s private home on fire, and the police later said they were assessing the damage across the several buildings the protesters took over.

In the days and weeks that followed, it became clear that the protesters’ victory was only partial.

Gotabaya Rajapaksa eventually fled the country on a military plane, first to the Maldives and then to Singapore, before arriving in Thailand on Thursday.

But that did not bring a clean slate: The man who replaced him, Mr. Wickremesinghe, is seen as a protector of the Rajapaksas’ interests. He immediately declared a state of emergency, sending the police after several protest organizers. He faces distrust as the country needs to enact difficult economic

reforms.

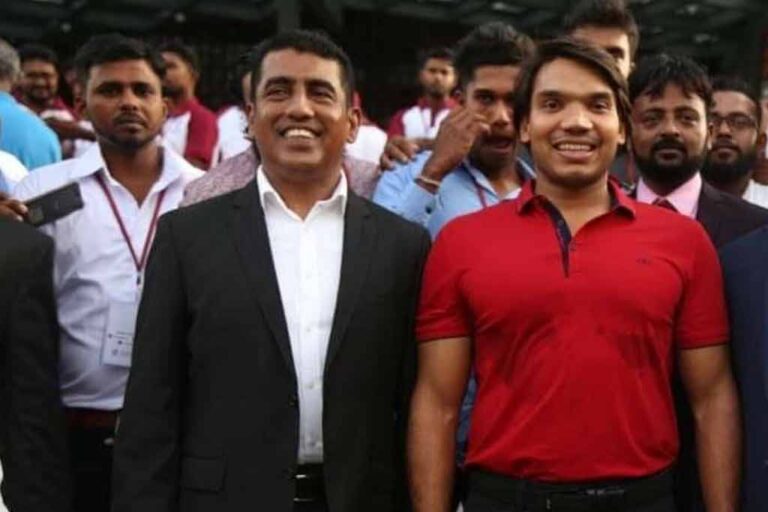

As Parliament voted to confirm Mr. Wickremesinghe as president, three Rajapaksas — Mahinda and Chamal, and Mahinda’s son Namal — were there to cast their ballots, as if nothing had happened.

“The band continues to play,” said Mr. Srinath, the taxi driver, “when the ship is sinking.”

The New York Times